Fine artist Morgan Weistling upholds the lineage of the golden age of illustration, along with the likes of Norman Rockwell, J.C. Leyendecker, and his mentor and instructor, Fred Fixler. While designing artwork and posters for Hollywood films for over a decade, Weistling honed skills he now uses as an independent painter and art instructor.

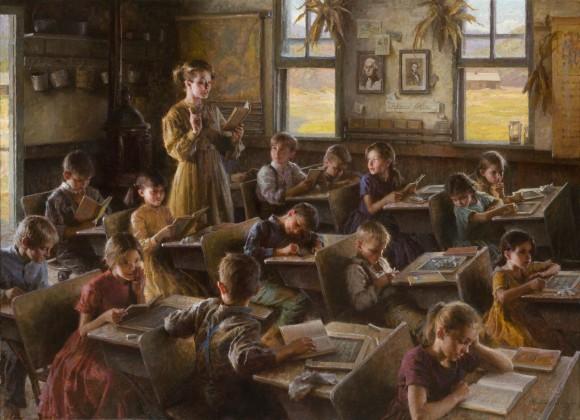

Characterizing Weistling’s works is simple. Perhaps from his youthful pastime of playing with stories and creating narratives, Weistling goes to great lengths to pull together all of the actors and elements for the background of a painting that, once woven together, become his often restful, soft, and iconic images of the Old West.

“I tried to paint images in different eras, but something about it never works. I keep coming back to the Western frontier,” said Weistling, jokingly adding that he had a time machine, but that it was stuck in the 19th century.