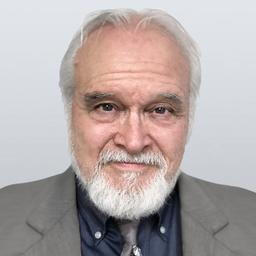

Composer Paul Schoenfield died on April 29, 2024, in Jerusalem. Almost no one in the press, musical or otherwise, noticed. The New York Times and Washington Post, both of which would almost certainly replate the front page to carry death notices of any number of pop musicians, carried no obituaries. In June, Schoenfield’s publisher released notice of the composer’s passing, and awareness of his death slowly made its way via word-of-mouth through the community to whom it meant the most: classical musicians.

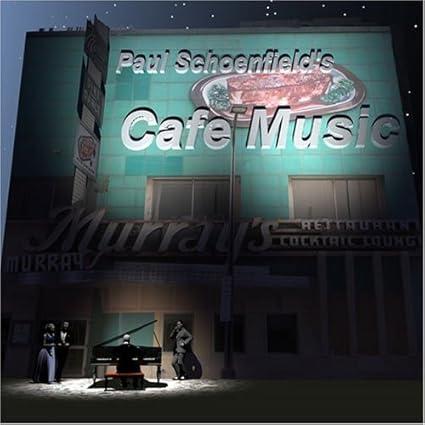

Schoenfield’s “Café Music” (1986), a vibrant score for piano trio (violin, cello and piano), is among the most widely played works of its kind written in the last 50 years. Listen to it in any of the many videos on YouTube and you'll understand why. It is emphatically not modern or post-modern. If a label could be applied, it might be “populist classical,” for the folksy/jazzy rhythms and the clearly tonal melodies that dominate its three movements. Schoenfield said he was inspired to write “Café Music” by memories of playing piano in a steakhouse, and indeed, the score sounds like a classical elaboration of tunes you might hear there.