This month’s 400th anniversary of the Pilgrims’ landing in New England will prompt renewed interest in their story—the flight from religious persecution in England, the long interim in friendly Holland, the trans-Atlantic voyage aboard the famed Mayflower, the ill-fated experiment in communal socialism, the remarkable governing document known as the Mayflower Compact, and more.

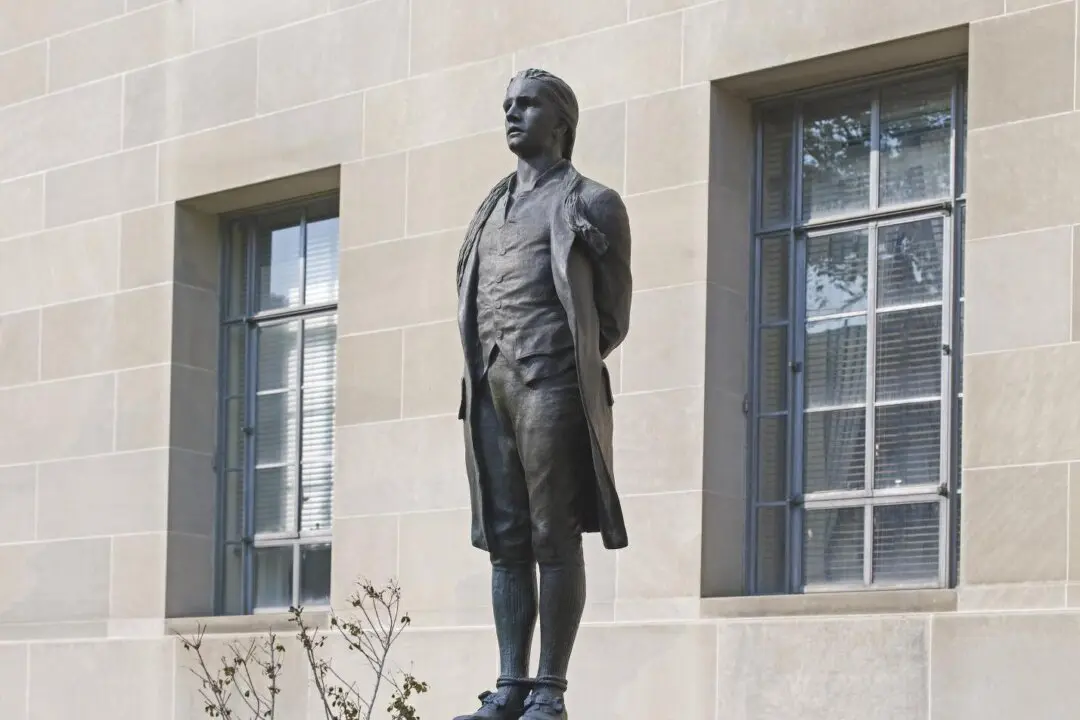

If you visit Plymouth, Massachusetts to see Pilgrim-related sites, you should not miss the Mayflower II, a full-size replica of the original vessel. Its much more recent story is almost as fascinating as that of its 17th-century counterpart and every bit the tribute to private initiative that the first one was. Enter a remarkable man named Warwick Charlton.