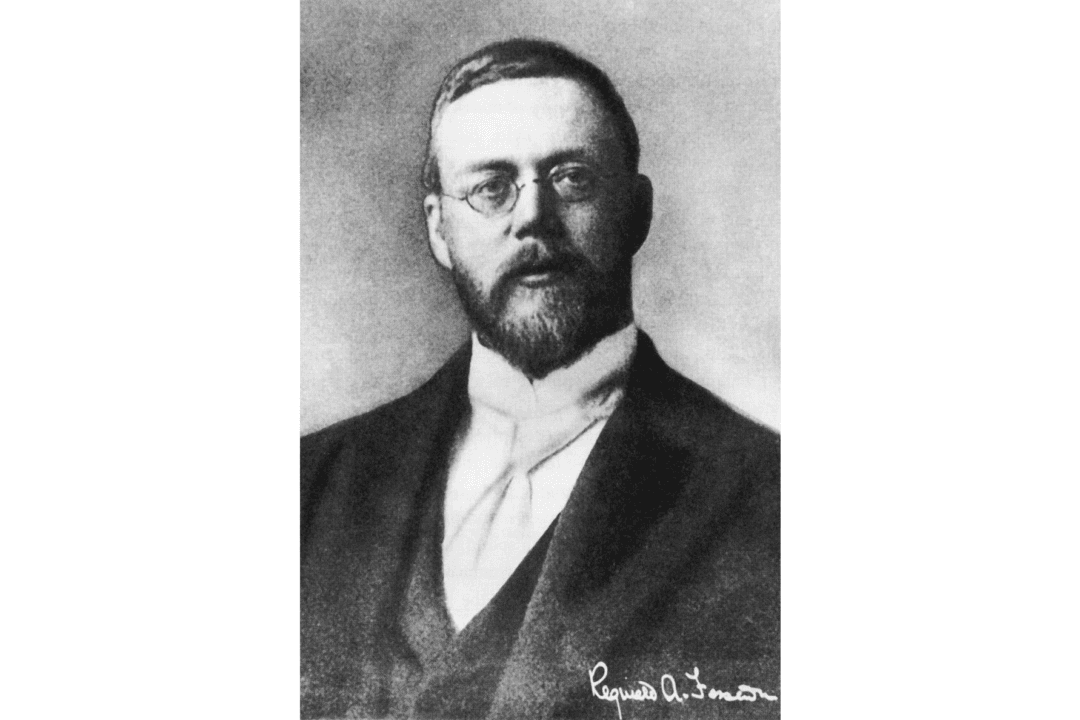

Reginald Fessenden (1866–1932) was born to an Anglican minister and a writer in East Bolton, Quebec. Fessenden received a fine education growing up, attending DeVeaux College, a kind of military prep school in Niagara Falls. It was during this time, at age 10, that he witnessed Alexander Graham Bell demonstrate the telephone in his Brantford, Ontario laboratory (the same place Bell would make the first successful long distance call—from Brantford to Paris).

In 1877, Fessenden left DeVeaux to attend Trinity College School in Port Hope, Ontario. After graduating, he attended Bishop’s College in Lennoxville, Quebec. He found success at the school, even teaching mathematics. His time there, however, was short-lived due to financial constraints. At 18, he accepted a position in Bermuda as the headmaster of the Whitney Institute. Around a year later, he decided to return to North America, but this time, he arrived in New York. His goal was to work for one of the nation’s most famous and brilliant inventors: Thomas Edison.