By Jake Sheridan

From Chicago Tribune

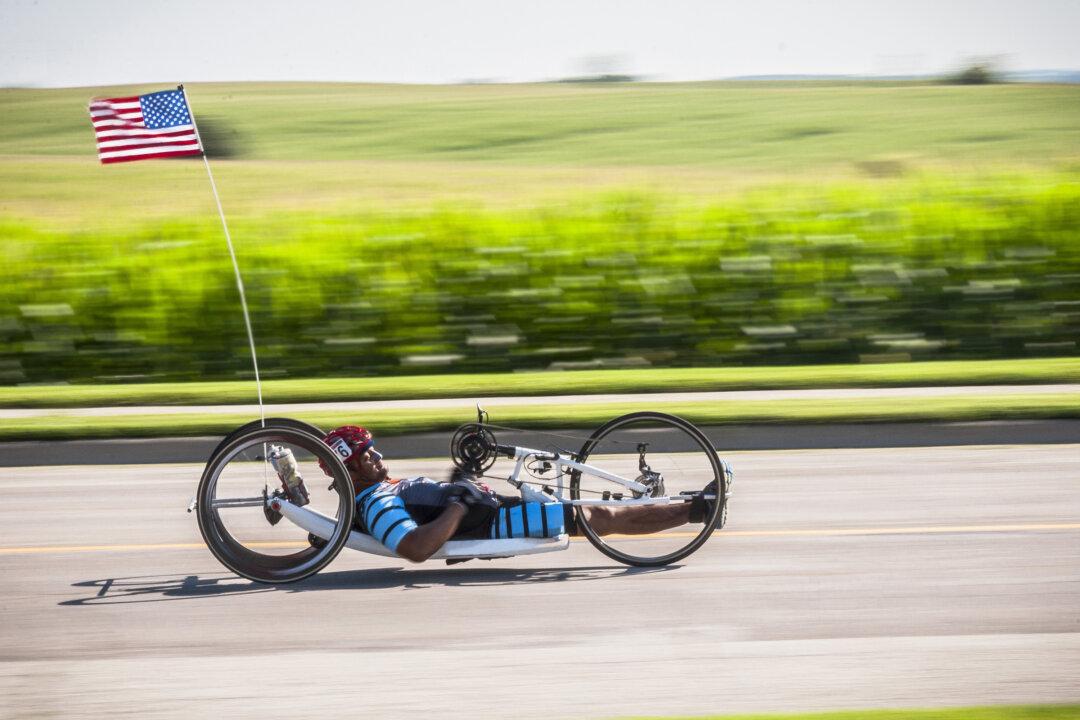

DAVENPORT, Iowa—A week before Daniel Griffin planned to cycle across Iowa, he faced a challenge most bikers never consider: How would he stay strapped into the left pedal?

DAVENPORT, Iowa—A week before Daniel Griffin planned to cycle across Iowa, he faced a challenge most bikers never consider: How would he stay strapped into the left pedal?