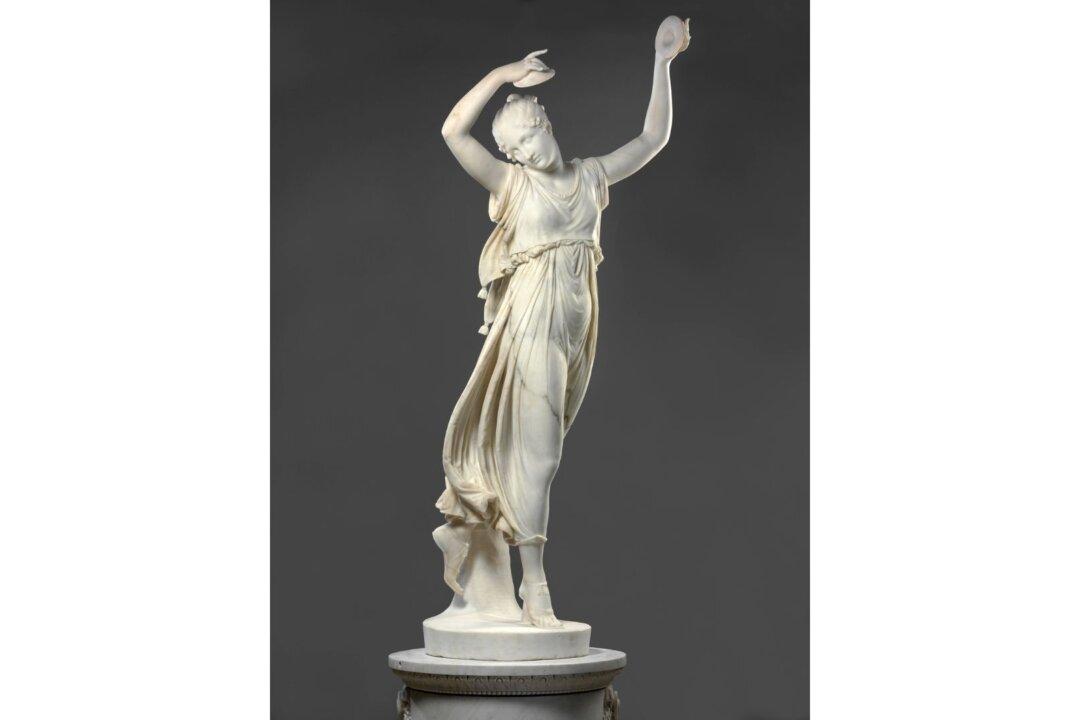

BERLIN—In the solemn silence of the Bode Museum, I can almost hear the music as Antonio Canova’s nearly life-size sculpture titled “Dancing Girl With Cymbals” effortlessly twirls and pivots on one leg before me. She dances with a lightness seen only in flight, raising her hands above her head for drama and balance, while playing her cymbals. She wears a delicate classical-style dress that skims her body, emphasizing every lithe move she makes.

This dancer’s peaceful presence belies the sculpture’s tumultuous past, having almost been destroyed in a fire and then lost for nearly 130 years before being rediscovered by chance in 1979.