If you were to peer into old family notebooks in which your relatives wrote down their recipes, what would you find? What culinary treasures long lost to the past would emerge?

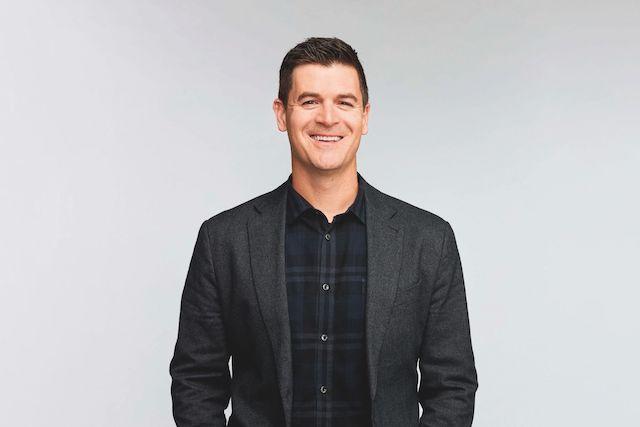

A few years ago, Halifax-based journalist Simon Thibault discovered the repository of recipes that Rosalie, his maternal grandmother, had kept. The recipes became a connection to his Acadian roots, but at the same time, the gaps he encountered demanded some detective work.