Firsthand accounts of overcoming adversity have always stirred something in me. Many years ago, I read Tom Brokaw’s then-newly published book “The Greatest Generation.” It’s a collection of very moving stories of those who faced the challenges and ravages of the Second World War. These were people who also grew up in this country during the Great Depression. To say they faced and overcame adversity—well, it kind of defines understatement.

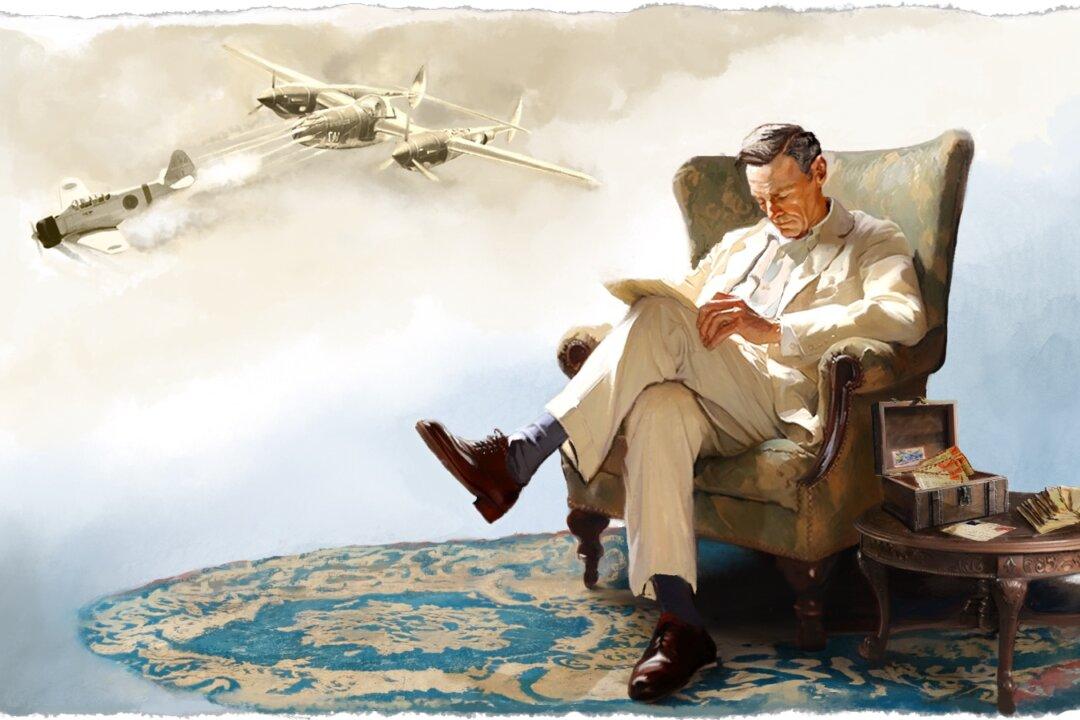

Both of my parents, who had married in 1940 in the middle of these two events, died around the same time Brokaw’s book was released. Among the things left to me by my folks was a small box filled with fading photographs, old newspaper clippings, and a batch of yellowing letters still in their envelopes. To my everlasting surprise, they revealed a story to rival any I discovered in Brokaw’s book and helped me understand a missing chapter of my own family’s story.