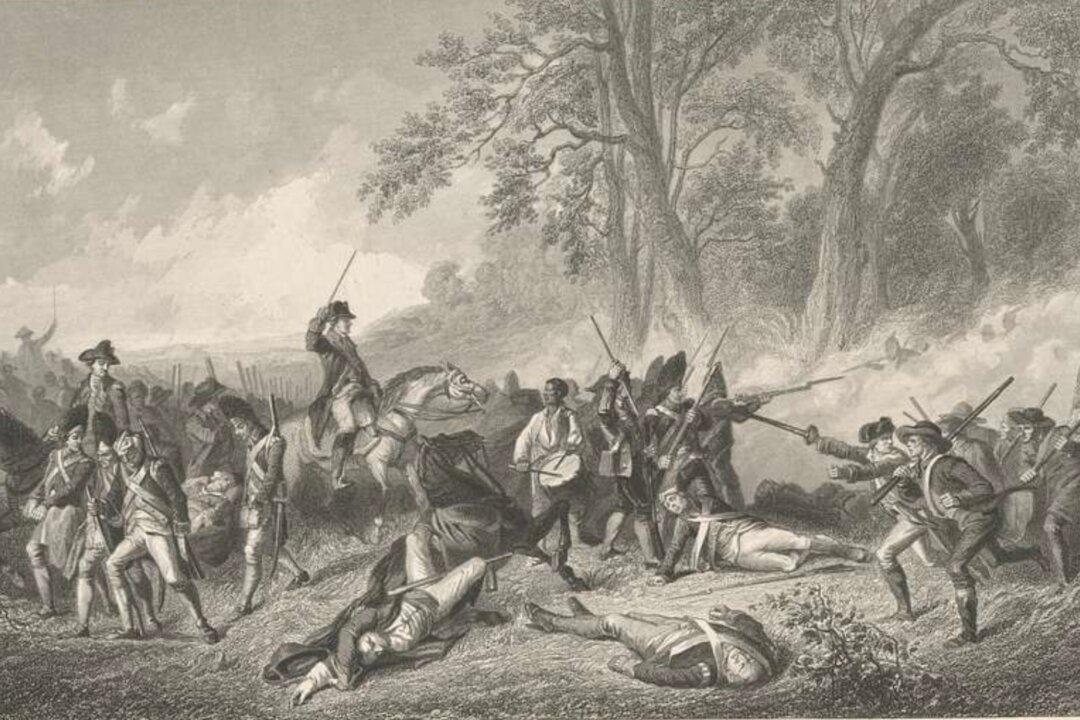

Every schoolchild once knew the story by heart: how a beleaguered George Washington became one of the sole surviving officers in a massacre that killed most of his army, but left him unscathed. How he took command when his general fell, rallied his troops as two horses were shot out from under him, and walked away with four bullet holes in his coat. While a modern reader is likely to think Washington merely lucky, his own account of the event ascribed a very different reason for his continued existence: it was nothing less than destiny.

A Doomed Expedition

At only 22, Washington became a distinguished veteran of the French and Indian War’s earliest engagements. His main talent? Surviving a siege by a much larger force at Fort Necessity and living to tell about it. Now a year later in 1755, he joined Gen. Edward Braddock’s newly arrived British army as an aide-de-camp.In late May, they set out through Ohio Country on a mission to capture Fort Duquesne (where Pittsburgh now stands). Braddock’s campaign was hopeless from the start. His arrogant attitude alienated both the local colonial governments and the Indian tribes, and his knowledge of warfare was based entirely on his experience of European battlefields. Washington recorded his view of Braddock in his diary: “He looks upon the country, I believe, as void of honor or honesty. We frequently have disputes on this head … as he is incapable of … giving up any point he asserts, be it ever so incompatible with reason or common sense.”