William Lloyd Garrison has gone down in the history books as being one of the first major leaders in the abolition movement of the 19th century. Although his opinions and anti-slavery views were very unpopular during that time, Garrison stood by his beliefs that all men are equal until his final days.

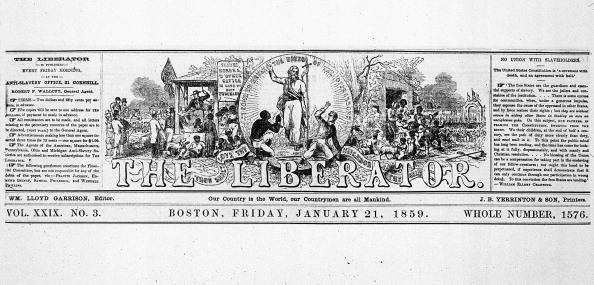

Garrison became most famous for publishing his own anti-slavery newspaper, The Liberator. Even though Garrison’s unpopular views often got him into trouble, he printed his newspaper for over three decades filling it with opinion columns and editorials against slavery and supporting the idea that all slaves should be freed immediately.