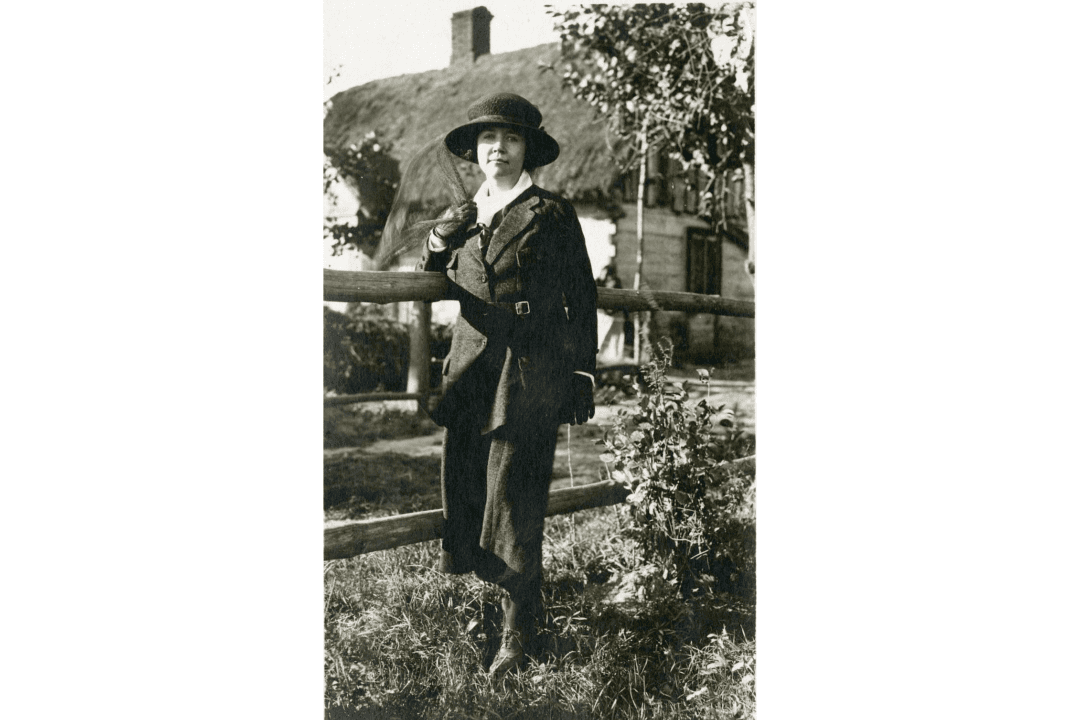

Today, Rose Wilder Lane (1886–1968) is best remembered, if she is remembered at all, as the daughter of Laura Ingalls Wilder, author of the beloved “Little House” books, children’s stories that Rose helped shape and edit before they appeared in public.

Rose Wilder Lane, circa 1905–1910. National Archives. Public Domain