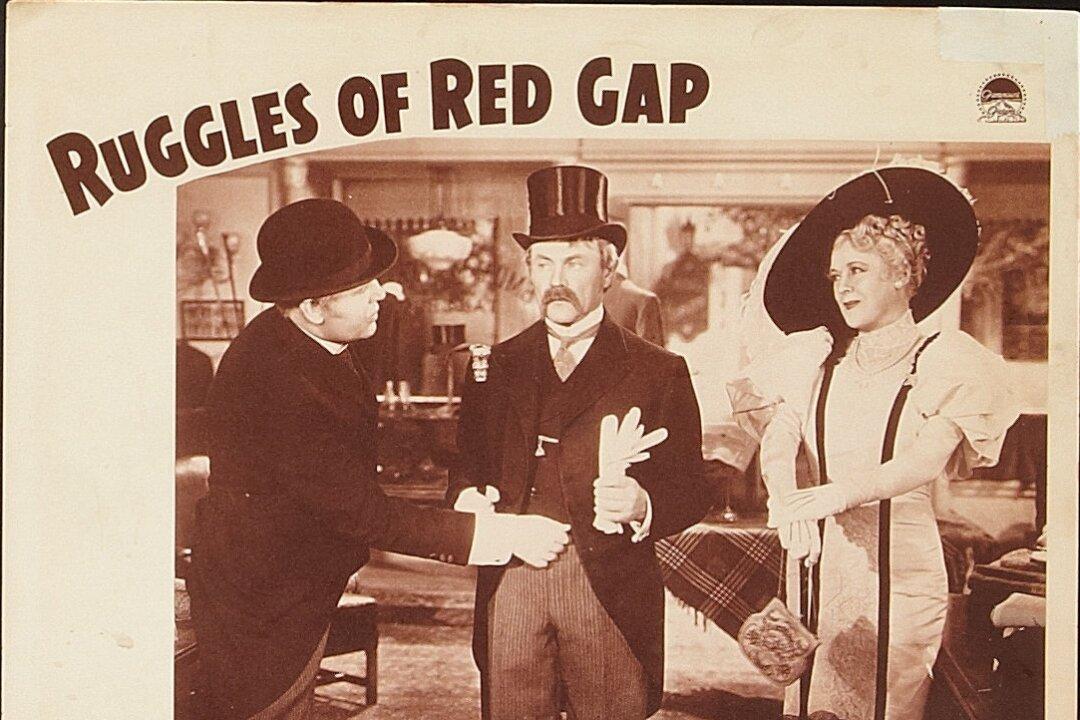

NR | 1 h 30 min | Comedy | 1935

If you’ve read P.G. Wodehouse’s side-splitting novels on the English valet Jeeves, you’ll appreciate the whiplash humor in “Ruggles of Red Gap.” If you haven’t, director Leo McCarey shows you what you’re missing.

NR | 1 h 30 min | Comedy | 1935

If you’ve read P.G. Wodehouse’s side-splitting novels on the English valet Jeeves, you’ll appreciate the whiplash humor in “Ruggles of Red Gap.” If you haven’t, director Leo McCarey shows you what you’re missing.