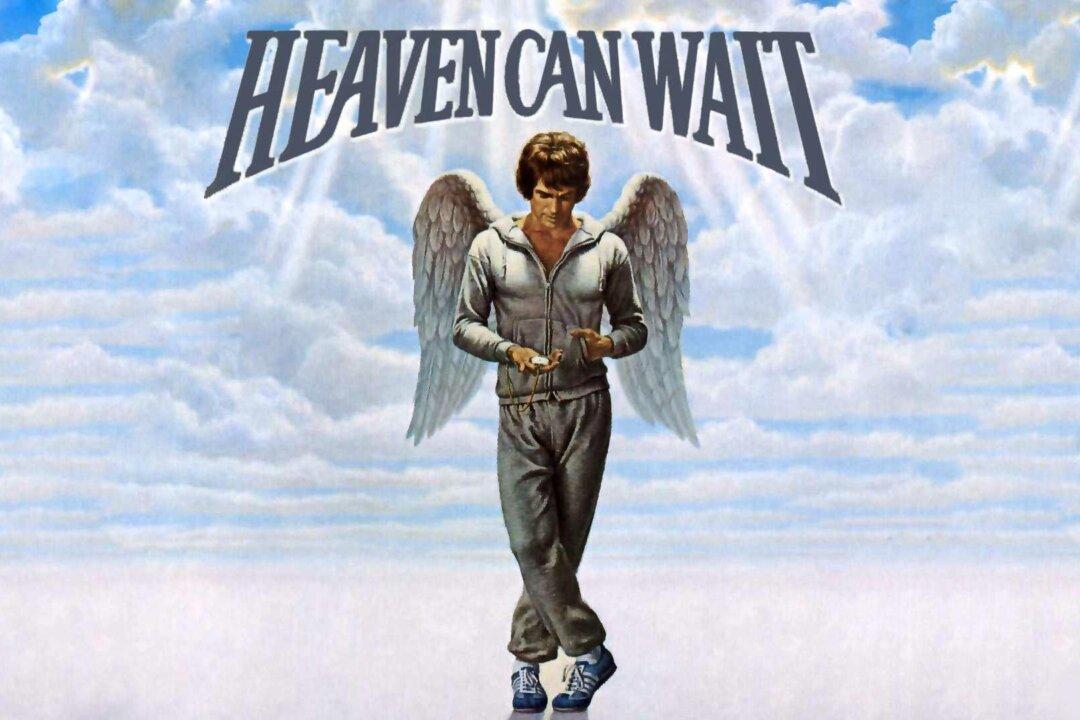

PG | 1h 41min | Drama, Comedy, Mystery, Fantasy | 28 June 1978 (USA)

After a decade of largely forgettable TV roles and low-performing features, Warren Beatty hit major critical and commercial pay dirt with “Bonnie and Clyde,” the first movie he both starred in and produced and that provided the launching pad for the remainder of his storied career.