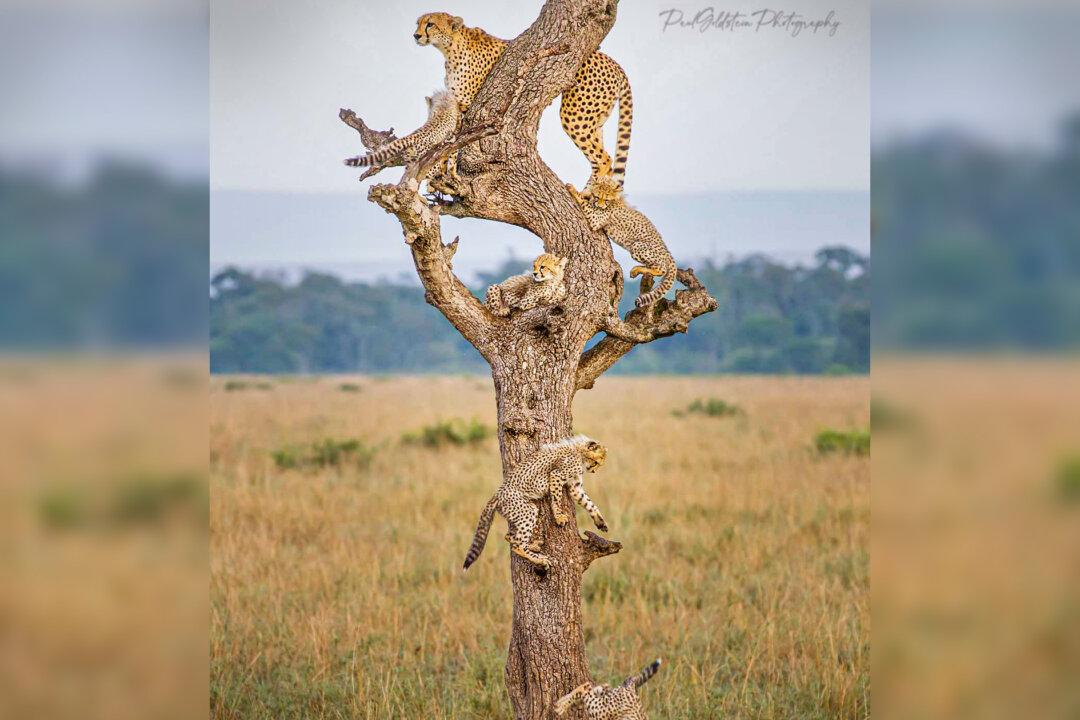

“You’re only as good as your last photograph,” said renowned wildlife photographer Paul Goldstein.

He spent nearly 30 years honing his craft and knows what must align to produce something truly original. He’s photographed jaguars in the Pantanal, tigers in India, a mother polar bear nursing, myriad animals in Africa, and aurora borealis dancing above 10,000-year-old grounded icebergs.