Disclaimer: This article was published in 2023. Some information may no longer be current.

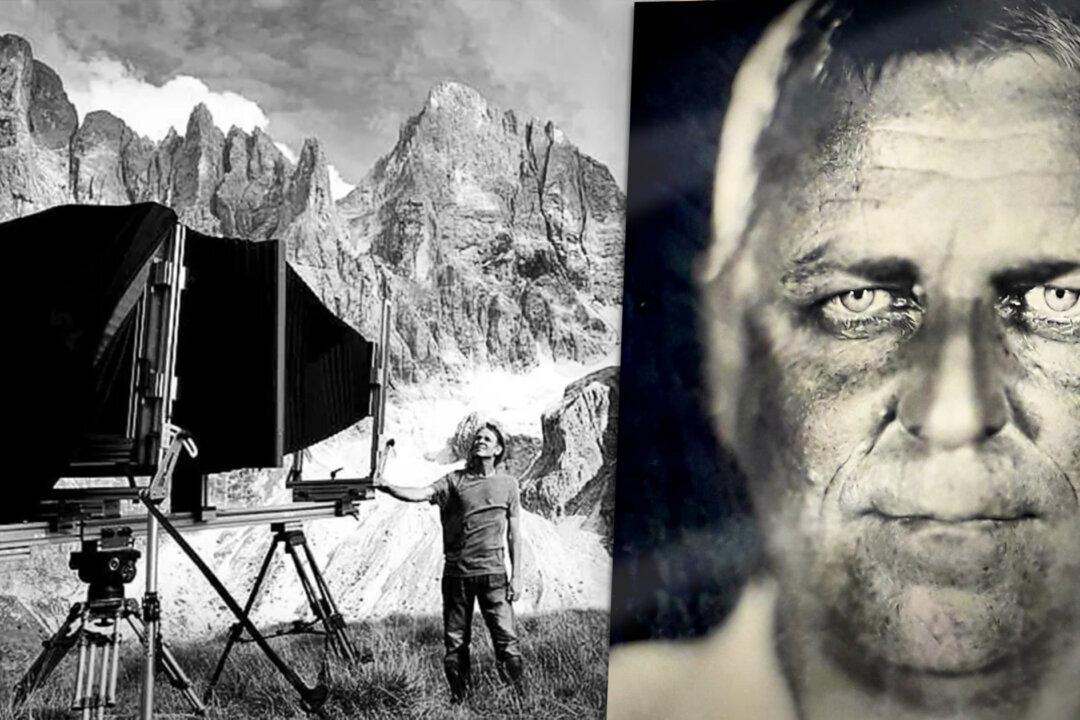

“She always says the camera found me and not vice versa,” photographer Kurt Moser said, denoting his collaborator, Barbara Holzknecht. “This project is more than work and it’s more than a project. It’s a lifestyle for us.”