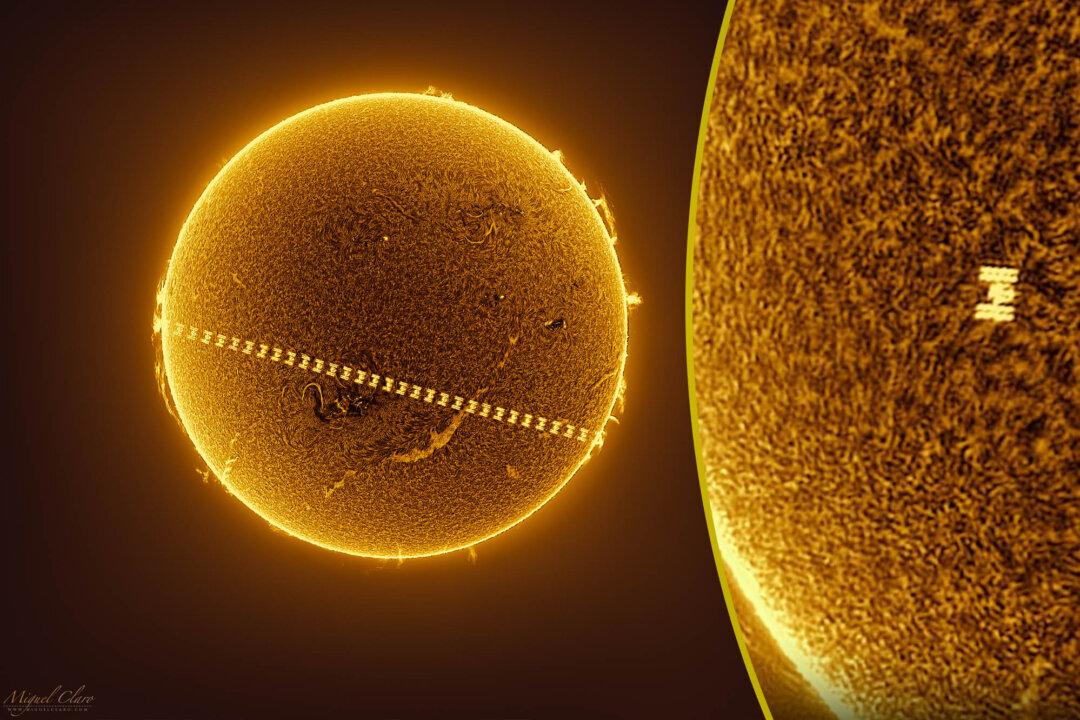

Miguel Claro has a dream for how all people under the great golden sun might converge and make the world a happier, more peaceful place—and he caught a picture of that dream on camera. In June, he set off into the wilderness near his home in Portugal and aimed his camera directly into the sun.

“The sun right now, at the moment, is amazing,” Mr. Claro, 46, an astrophotographer, tells The Epoch Times, speaking of what he describes as a period of solar instability that recurs dependably every 11 years.