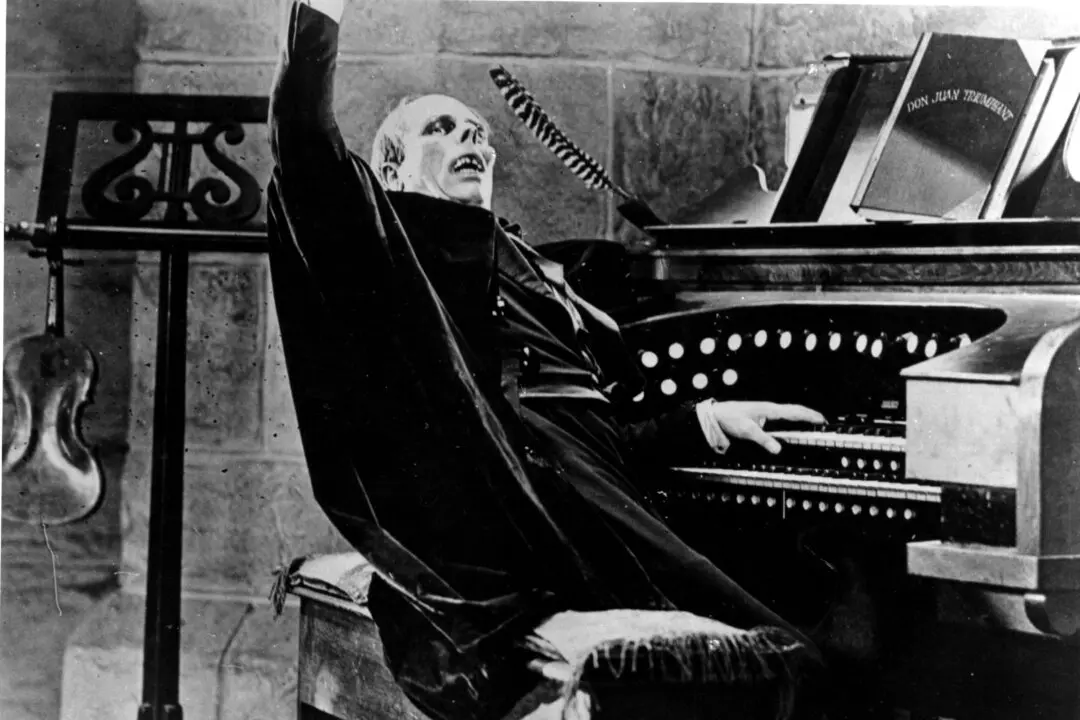

As a child, I had a cassette tape called “The Sounds of Halloween.” It had all the creepy sound effects one would expect: creaking doors, moaning ghosts, eerie laughs, a Dracula voice, and a few popular songs like “Monster Mash.” It also had something else: The first side began with J.S. Bach’s “Toccata and Fugue in D Minor.” Bach’s piece is forever associated in my mind with the holiday.

Bach himself, of course, would have thought this exceedingly strange. BWV 565, written sometime around 1708, was originally intended to accompany worship during a church service.