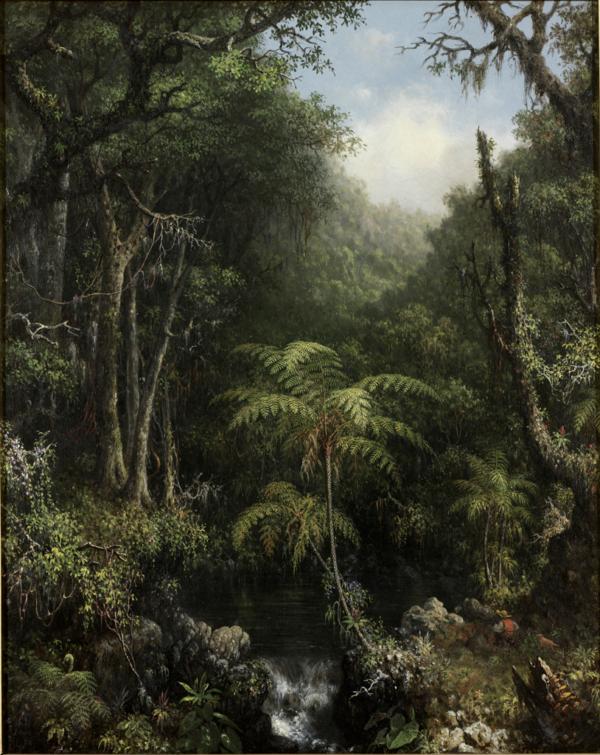

Flora covers every inch of land in American artist Martin Johnson Heade’s “Brazilian Forest” painting, creating a dense habitat for all manner of unseen fauna. In the center, a tree fern’s giant fronds fan out every which way, appearing like a broken umbrella that Heade used to draw our attention to the gushing waterfall below and the vast, misty, mountainous forest beyond. Lichen- and creeper-covered trees in the middle ground climb skyward beyond the picture plane. Here, nature reigns supreme, and Heade put this into perspective by adding a hunter in a red waistcoat and wide-brimmed hat who wades waist-deep through vegetation. His hunting dog follows along, ever alert to the choir of jungle animals.

“Brazilian Forest,” 1864, by Martin Johnson Heade. Oil on canvas; 20 inches by 16 inches. RISD, Providence, R.I. Public Domain