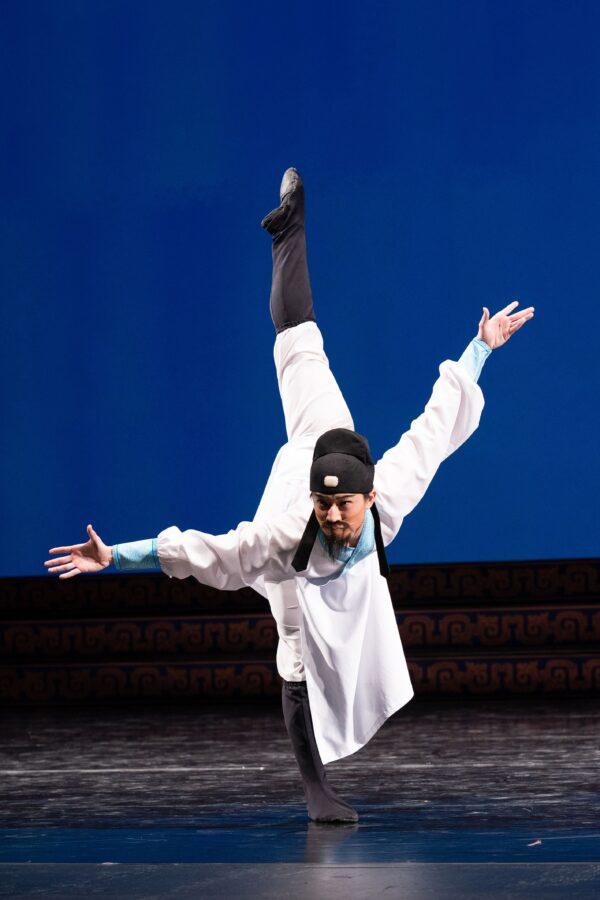

“I was the kind of kid who couldn’t sit still; I was always moving,” Zhang said. At age 8 or 9, he attended a classical Chinese dance performance where he saw his older cousin flip into the air—and seemingly stay there for a while—before coming back down to the ground. He was in awe, and set his sights on becoming a dancer.

“I grew up in the West, so it was a little harder to grasp that Chinese feeling,” he said. His teachers would demonstrate a movement and he would copy it to a T—or so he thought—but they were not satisfied. “You should feel the inner meaning of the movements!” they would tell him, and it would go over his head. “You’re executing the move, but you are not dancing,” they told him, or worse, “That just looks bland.” Slowly, he started to understand.

“This is a great opportunity to improve myself,” Zhang said. “From choosing the music to the choreography, the whole process really reveals your strengths and weaknesses.”

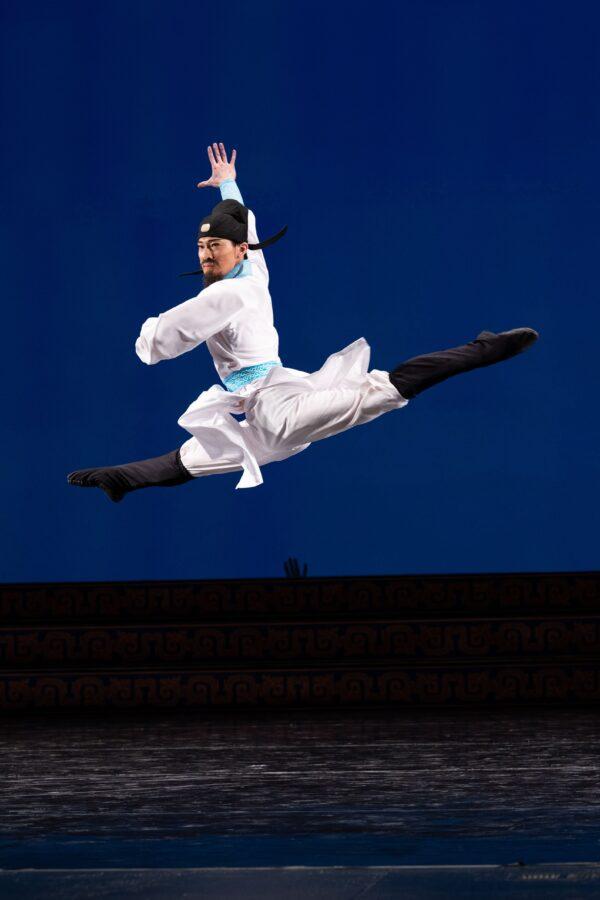

The ‘Immortal Poet’

Tang Dynasty poet Li Bai is one of the artists that brought about the “Golden Age of Chinese Poetry,” and his piece “Drinking Alone by Moonlight” is one of the best-known pieces of Chinese poetry, and has been translated into English and many other languages. Zhang has set the event of Li Bai penning this poem into dance.“When I heard the music and saw the movements, I was really taken by it,” Zhang said. He felt he could relate to this poet, and sought to adapt the movements and choreography to better suit him.

From the Heart

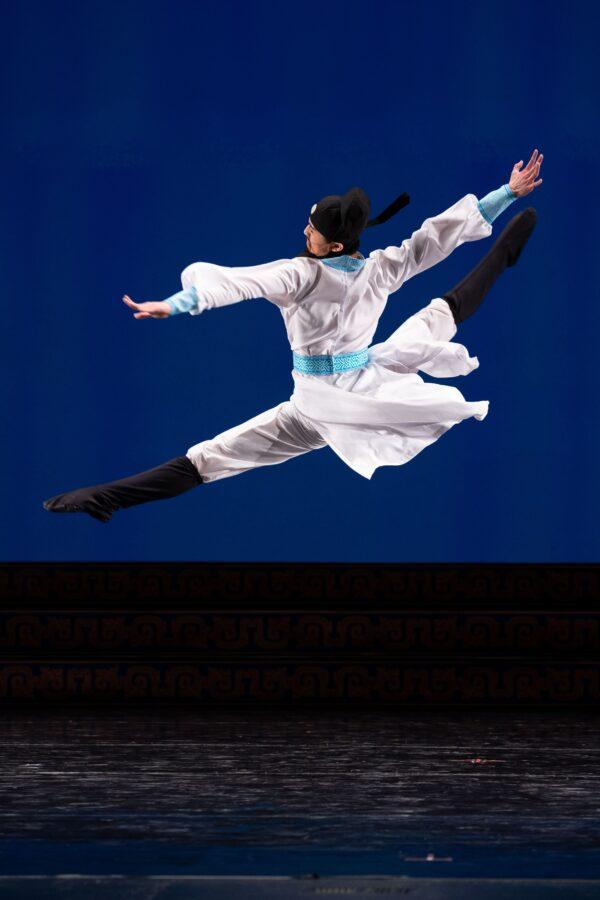

A new component of the dance curriculum at Shen Yun and Fei Tian Academy of the Arts—and something the competition judges will look at—is the method of “body leading the hands.” This is a technique often talked about in the dance world, as it increases the expressiveness of a dancer’s upper body movements, while also elongating the limbs and creating a more efficient way of movement, use of force, and use of energy. But while this method of movement is ideal, Shen Yun and its academy are the first to include it as part of their dance pedagogy.“It’s about how you use your force, and how the force starts. You start from the innermost part—your body becomes part of your arm,” Zhang explained. “You have to begin from the heart, from this inner core here, which puts into motion your outer limbs. And in this way, your entire body seems light, and the movements are so clean.”

Classical Chinese Dance

In addition to the “body leading the hands,” Shen Yun dancers use a method of the “hips leading the legs,” which has similarly never made it into dance pedagogy but has a similarly beneficial effect on a dancer’s lower body movements.The new development has been especially enlightening for these students of classical Chinese dance, because this dance form is all about expressing inner feelings and every artist of classical Chinese dance is pursuing the most beautiful way to do so on stage.

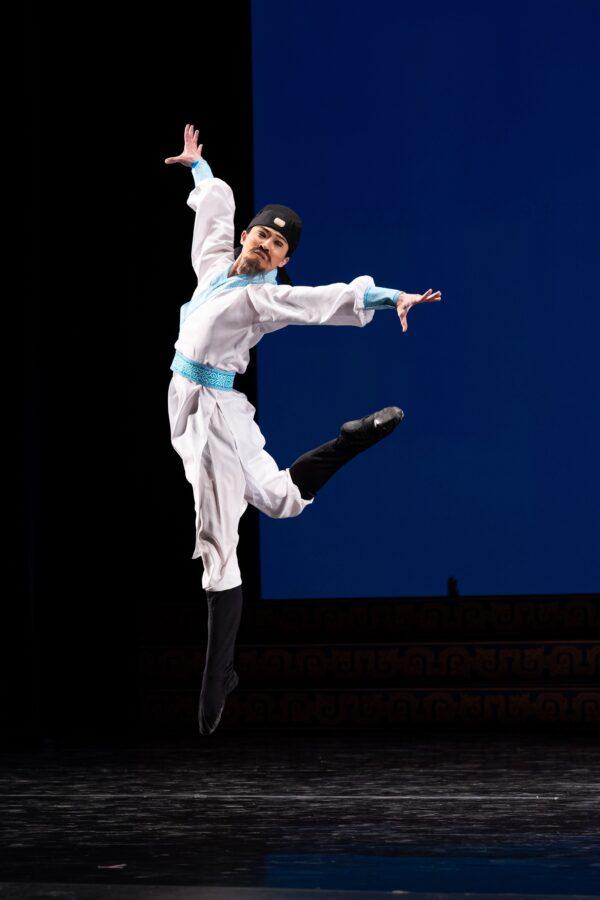

“Every movement has a meaning, every gesture has something behind it,” Zhang said. “Dance is a way to convey thoughts and emotions—teachers have told me, everything on your heart will come out through your emotions.”

This is reason to cultivate a heart of kindness, Zhang said. “If you’re feeling annoyed, it’ll come through.” Instead, he seeks a feeling of calm and inner peace to give to the audience. “If you can hold that peace you can express it.”

“Dance requires you to be very willing,” Zhang added. “You need to have an open heart.” From being willing to do the strenuous stretching required to stay limber, to being willing to put your inner feelings on display on stage, you have to constantly meet your challenges with a positive and accepting attitude, Zhang has learned.

“You have to really face yourself,” he said.