In 1963, at the request of its editors, President John F. Kennedy submitted a preface for the 16-volume “The American Heritage New Illustrated History of the United States.” Following his assassination, American Heritage reprinted this preface, “On History,” in its February 1964 issue of the magazine.

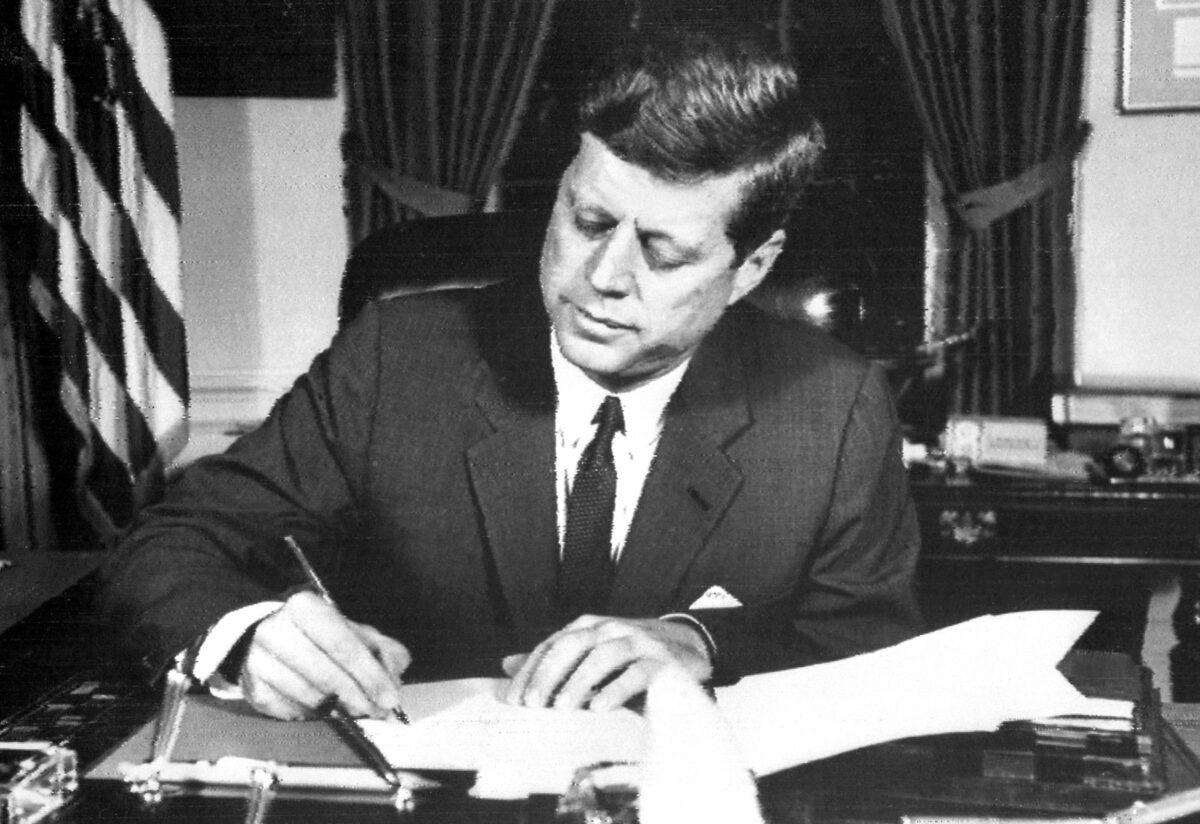

President John F. Kennedy signs the order for a naval blockade of Cuba on Oct. 24, 1962, during the Cuban Missile Crisis. AFP via Getty Images