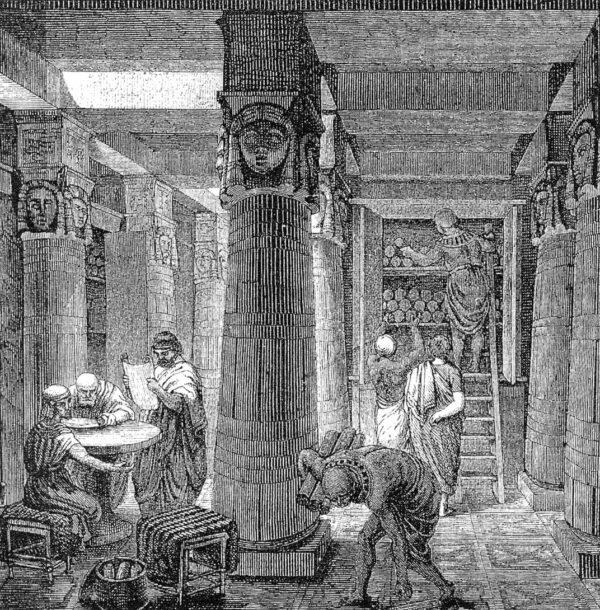

Libraries, private and public, have long served as treasure houses of culture. The most famous library in the ancient world was the Great Library of Alexandria. That vast collection of scrolls helped make the city a chief intellectual center in the Mediterranean for centuries, until the library entered a slow decline because of a fire and a lack of funding during the Roman period. The emperor Trajan founded The Bibliotheca Ulpia in Rome in A.D. 114, another famous repository of literature and historical documents.

"The Great Library of Alexandria,” 19th century, by O. Von Corven. From “The Memory of Mankind,” Oak Knoll Press. PD-US