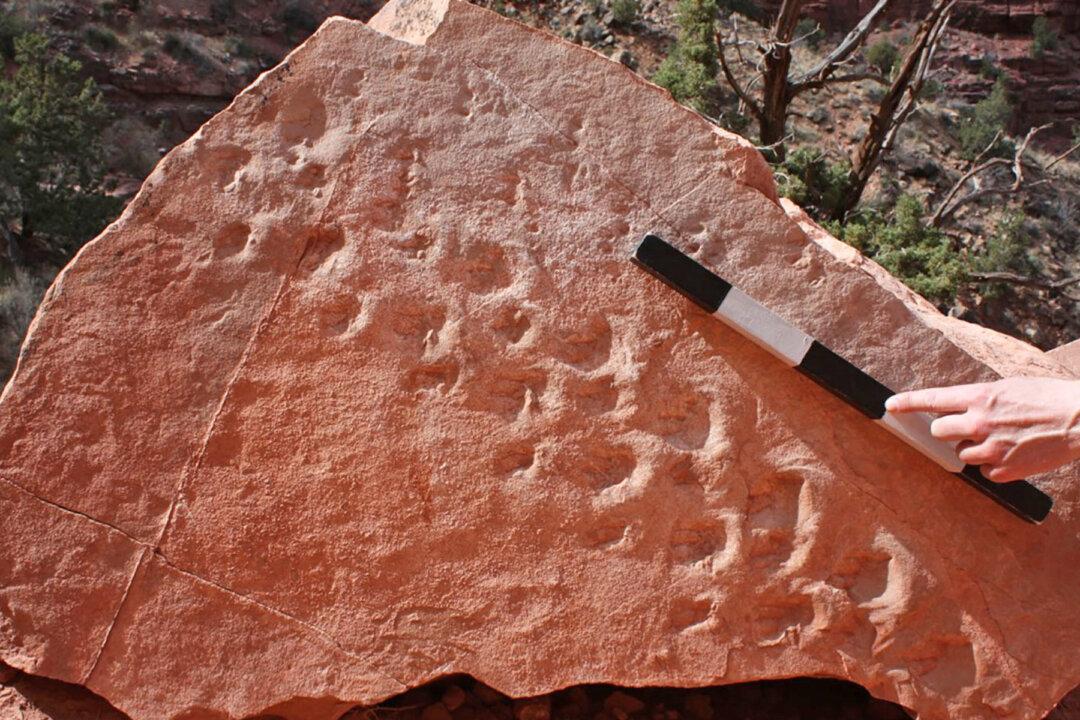

Finding fossil footprints at the Grand Canyon isn’t particularly unusual. The expansive stretch of red rock is home to an array of formations containing preserved remains of the past.

But a discovery made by a geology professor turned out to be a bigger deal than he could have imagined: what he stumbled upon were the oldest vertebrate fossil tracks ever found at Grand Canyon National Park—about 313 million years old.