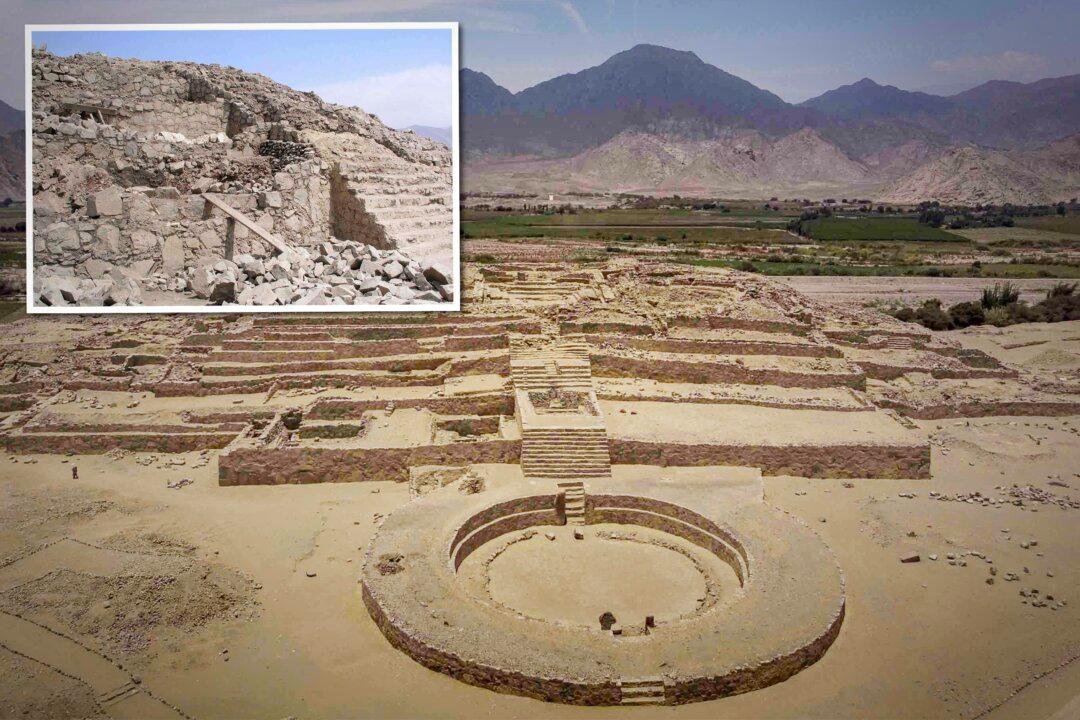

A few miles up a desert valley road from the roaring Peruvian coastline and irrigated fields north of Lima, there once was a stone city with pyramids. Their dust-blown outlines and stepped bases are still seen, their roofs long weathered away.

The peoples who lived, celebrated, made music, and worshipped here—when the pyramids of Egypt were being built—are today long forgotten.