The name “Mark Van Doren” isn’t likely to top most people’s lists of famous literary critics. Yet this somewhat forgotten scholar—and more importantly, lover—of literature has much to teach us about the right way to think, study, and comment on literature. Van Doren (1894–1972) fought against the overly technical, scientific method of reading poetry that developed in that latter half of the 20th century. The new method tended to isolate literature from life and the wider world. Perhaps unwittingly, the New Criticism and its successors often stifled the joy of reading and commenting on literature.

Authenticity Is Key

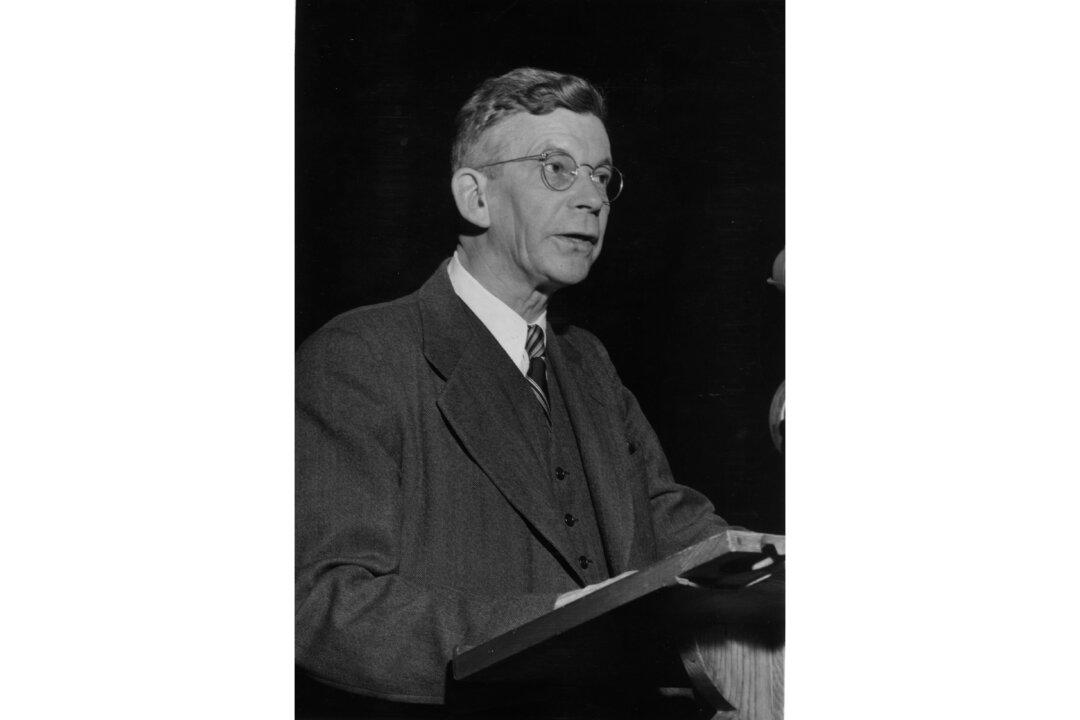

Van Doren, an angular man with a grave expression, was a professor of English at Columbia University for almost 40 years and literary editor of The Nation. He wrote a number of books and essays on great works of Western literature, including volumes on William Shakespeare, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and John Dryden.A talented poet in his own right, Van Doren won the 1940 Pulitzer Prize for Poetry for his “Collected Poems 1922–1938.” As a teacher, he influenced a generation of notable writers and thinkers, including John Berryman, Richard Howard, Allen Ginsberg, John Senior, and Thomas Merton.