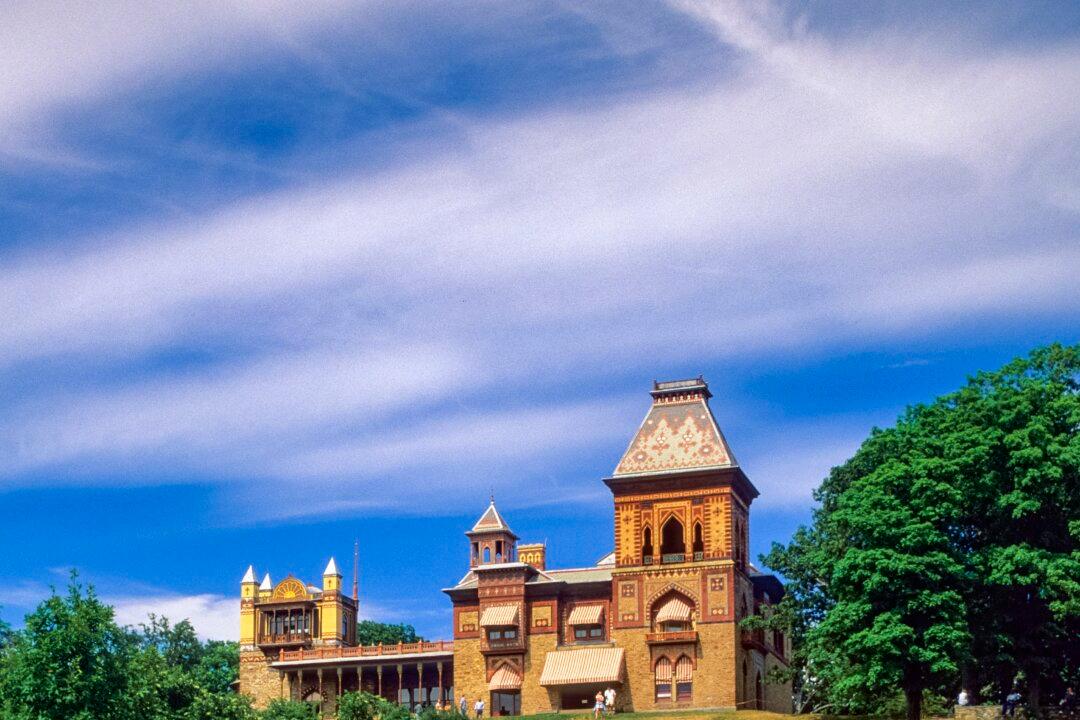

On a ridge overlooking the Hudson River, artist Frederic Church composed his last, and perhaps grandest, work: a home and grounds for his family. He purchased the land above his first home, “Cosy Cottage,” before his trip to the Middle East and Europe. “I have just purchased the woodlot on the top of the hill. I want to secure if possible before I leave every rood [measure] of ground that I shall ever require to make my farm perfect.” Church’s vision was ambitious; not only did he want to expand his working farm, Church set out to create a foreground for the magnificent scenery in the distance—linking together a series of vistas with landscaped carriage roads. Church had formerly served as the park commissioner of Central Park and was fascinated with the possibilities of creating beautiful landscapes, working with the beauty already present in the natural world.

The hilltop that Church purchased was the same location that he and Thomas Cole visited when he was under the tutelage of Cole. The property overlooked Cole’s home on the Hudson River, and they would often walk there and sketch. Many of Church’s earliest works were inspired by the scenes from this particular site, and it was that very landscape that had started him in his work. Though Church was once the most famous artist in America, his popularity (and career) waned in the 1870s. There was no longer a great demand for his large canvases, and commissions for his paintings of antiquities decreased in frequency. His rheumatoid arthritis also made painting more difficult. As the world forgot about Frederic Edwin Church, the great artist still had the means to devote himself to his family and the building of their amazing estate—a task he set about with great energy.