By Mary Ann Anderson

From Tribune News Service

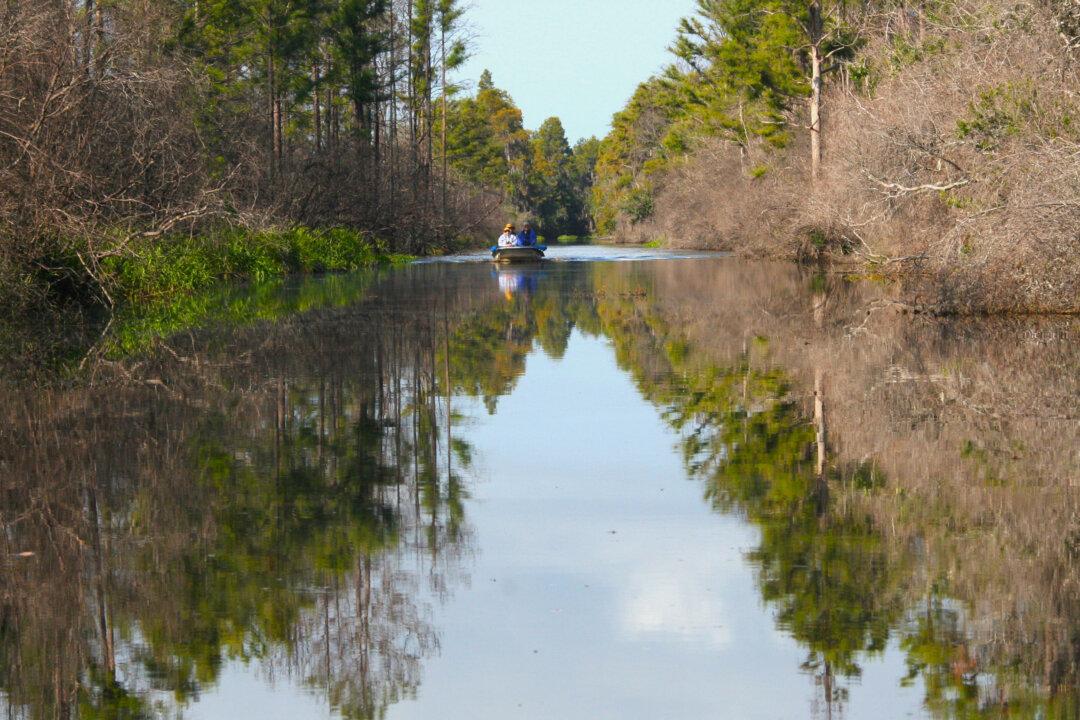

Call it what you will — primordial, mystifying, daunting, backwater or, above all, magnificent in that swamp sort of way — the Okefenokee Swamp is one of Georgia’s most beloved treasures. Covering some 700 square miles in southeastern Georgia and the very northern reaches of Florida, the Okefenokee, whose name means “Land of the Trembling Earth” in the Creek language, is now part national wildlife refuge and part privately owned park that is widely known for harboring an incredible cache of biological and ecological wonders.