The Gothic era, an epoch so marvelous, magical, and perplexing that to this day it has never been fully fathomed, triggered the rebirth of yet another magnificent period. That rebirth, of course, was the Renaissance, which discovered the great cultures of our forebears, Greek and Roman alike, and polished them off with Christ’s maxims. And so, the first literary giants of Christianity stepped onto the stage and Humanism was born.

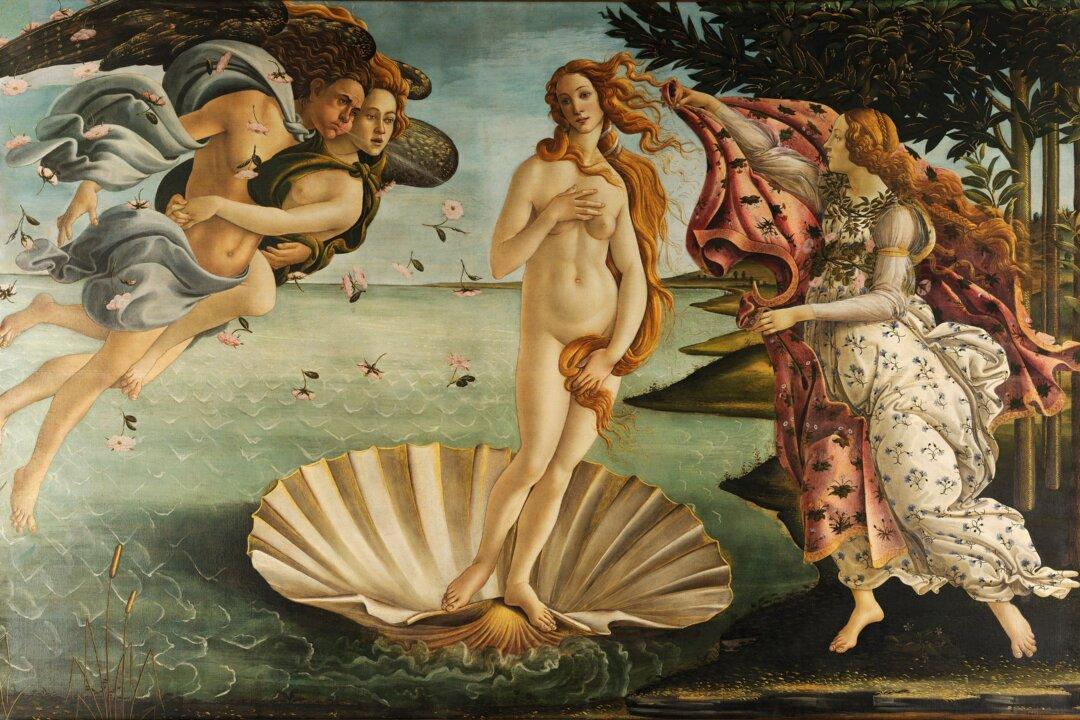

Amazing heroines such as Petrarch’s Laura and Dante’s Beatrice captivated the hearts of educated Italy and those beyond. As a result, the veneration of the weaker sex received yet another elevation of their status. The first was the highly romantic if not quasi-divine spheres the female reached by way of the troubadours. But now dukes, popes, counts, and condottieri, all with an infallible sense for beauty and elegance, had their spouses, daughters, and mistresses educated, usually by the best scholars money could buy.