Commentary

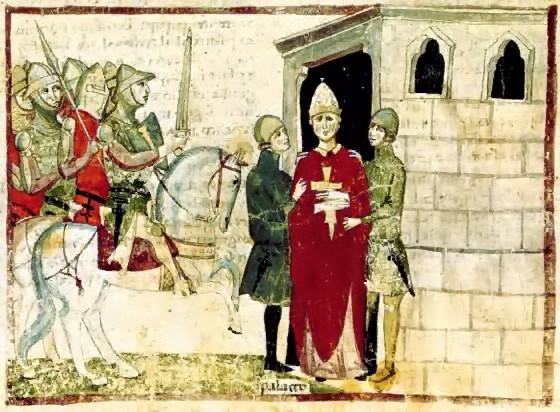

On Sept. 7, 1303, a French military force which had crossed into Italy seized the pope at his summer palace at Anagni, south of Rome. The soldiers dragged him from his throne, beat him, and threw him in a jail cell, intending to take him back to France for trial. What had prompted such an extraordinary turn of events?