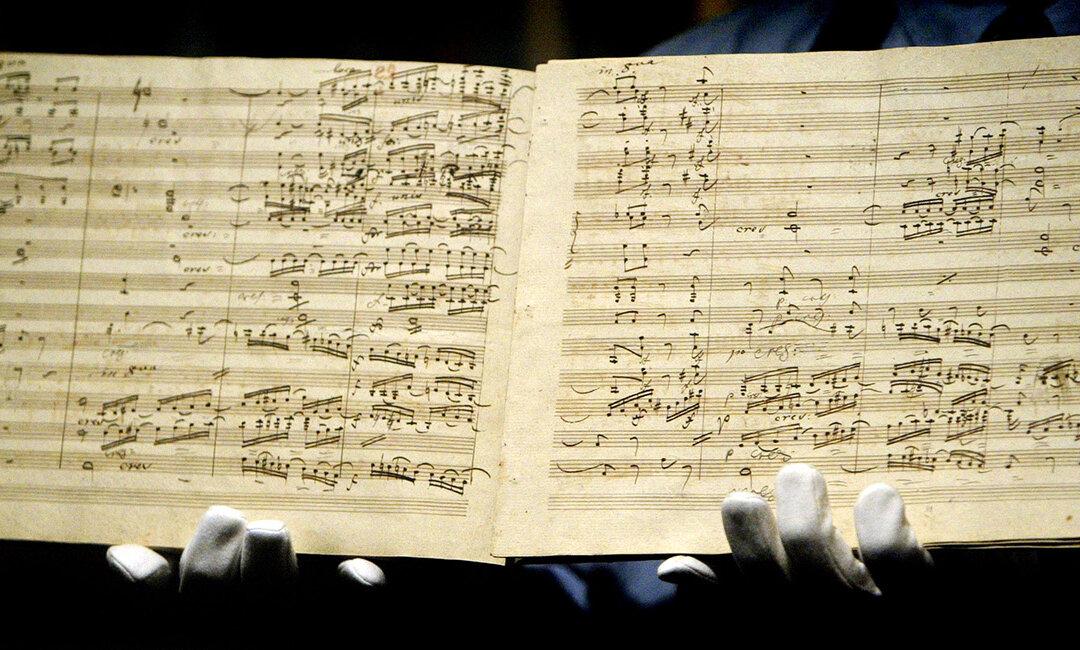

The last symphony that classical composer Ludwig van Beethoven ever penned is considered his crowning achievement. Symphony No. 9 was more than a piece of music to the German virtuoso. It represented in dashing, melodic form a lifetime of hardships, triumphs, and his lifelong dance with “fate’s hammer.”

The symphony’s last movement, “Ode to Joy,” was a composition more than 30 years in the making. The inspiration for the famous piece first struck Beethoven during his college days while studying the poetry of one of his favorite writers, Friedrich Schiller.