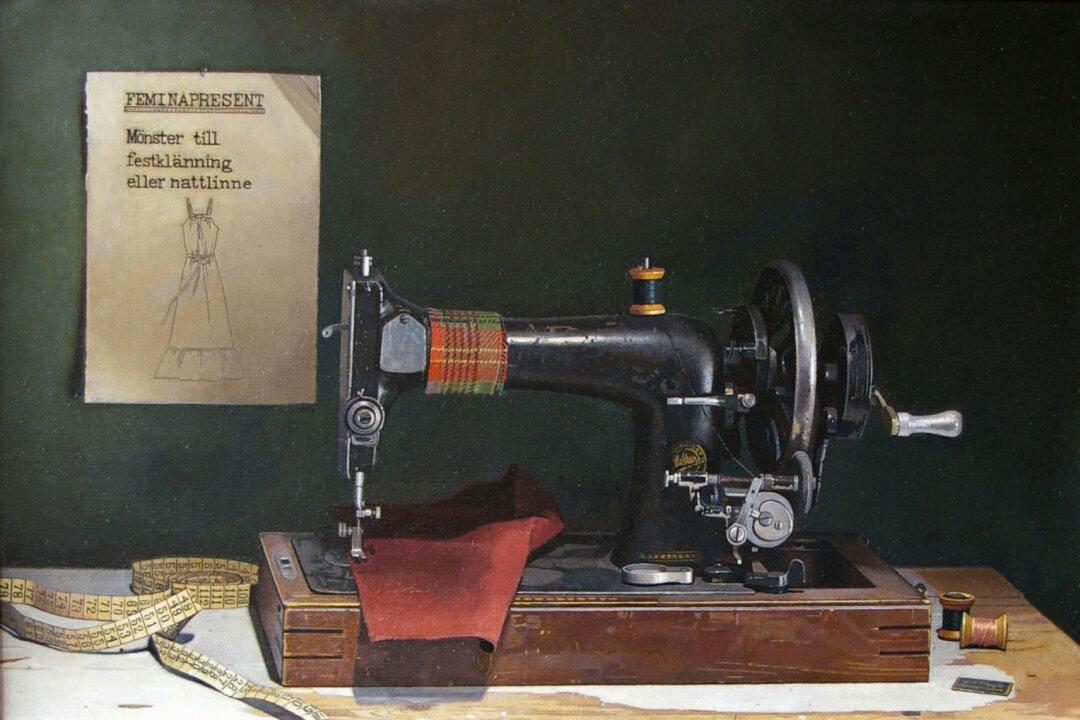

BERGEN, Norway—Norwegian artist Atle Skudal’s paintings capture significant moments in people’s lives. He often includes objects that are family-related or that used to belong to someone close to him, but beyond these close connections is a bigger story.

The artist Atle Skudal in his studio in Bergen, Norway, on Aug. 8, 2018. In the background is a work in progress, a bee-themed still life. Susanne W. Lamm/The Epoch Times