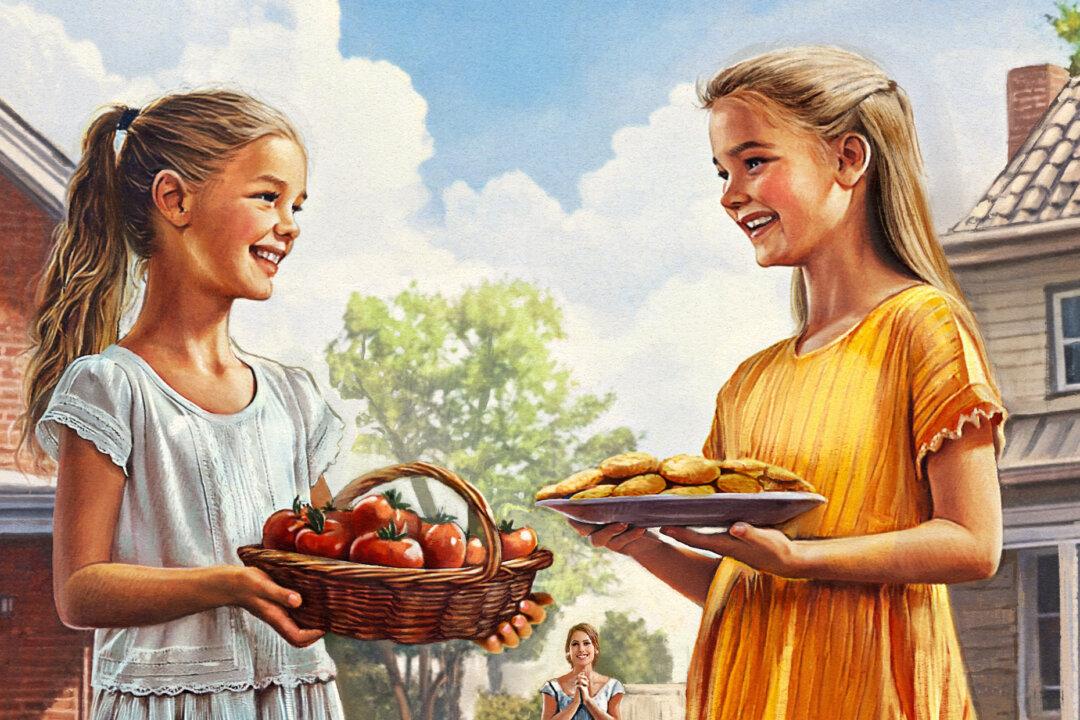

My entire family was invited to a graduation party over the weekend. Such an invitation is nothing out of the ordinary; what made this invitation unique was that the graduate was a third-generation member of a long-standing friendship—his grandparents were neighbors of my parents for more than 40 years.

This invitation would naturally seem rather strange to the casual observer—a coattail acquaintance, if you will, out of whom the graduate was simply trying to squeeze another gift.