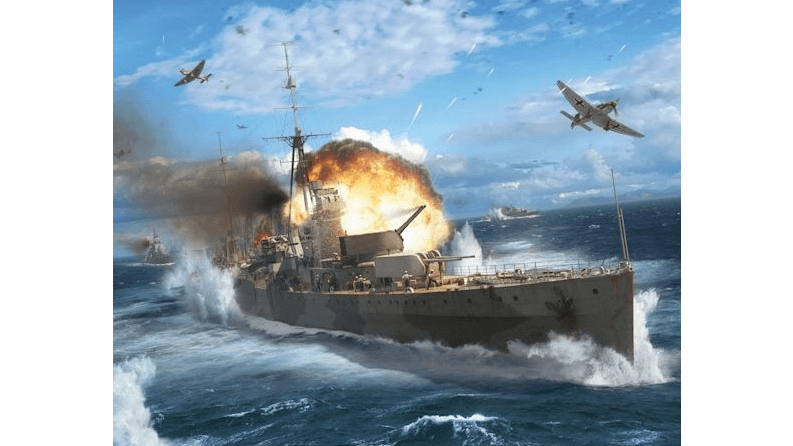

In much the same way as Dunkirk, the Battle of Crete was an event of heroism during a retreat. Angus Konstam has presented a battle that took place on the Eastern Front of World War II in 1941, but delves into the details of all that surrounded the British defeat. In his new book by Osprey Publishing entitled, “Naval Battle of Crete 1941: The Royal Navy at Breaking Point,” we get an insightful breakdown into the commanders, the warships and aircraft, and the tactical maneuvers between the British Commonwealth, the Italians, and the Germans. All of the aforementioned are perfectly illustrated by Adam Tooby.

Mr. Konstam gives a brief overview of what immediately preceded the Battle of Crete, which took place at the end of May. Operation Demon was a late-April Allied effort to evacuate troops from the Greek mainland. By many accounts, it can be considered a success, despite losses of several warships and hundreds of troops. But the operation did, according to the author, safely evacuate approximately 50,000 Allied soldiers. And this is where Mr. Konstam helps the reader understand why the Battle of Crete was set up for near disaster.