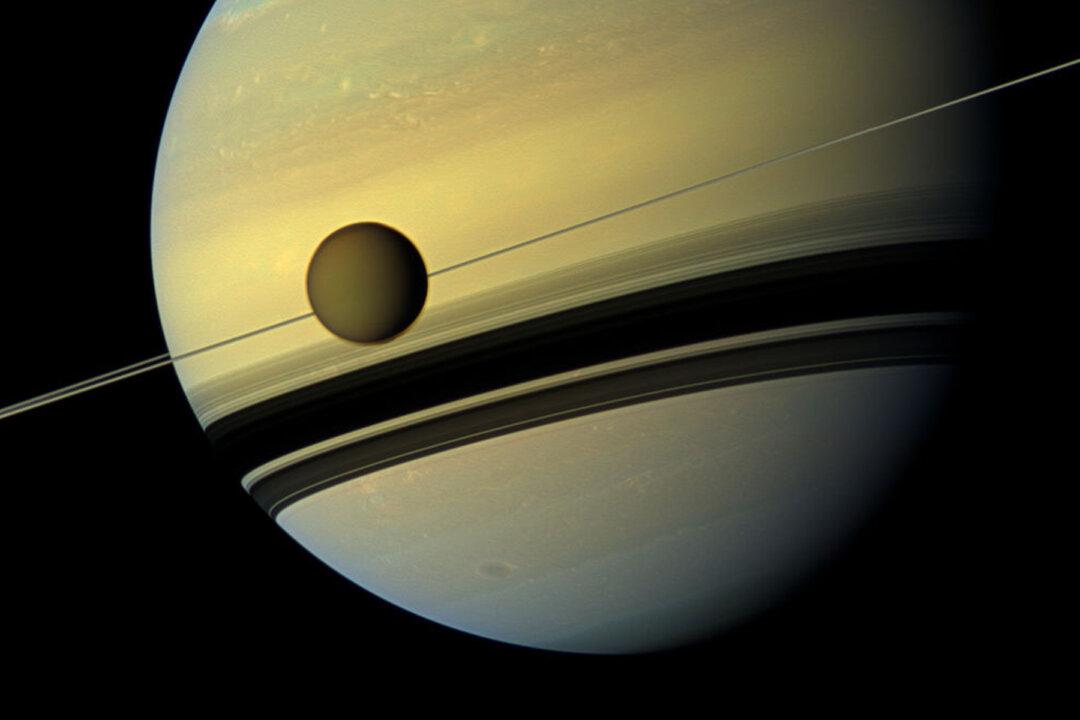

NASA’s Cassini probe crashed into the surface of the solar system’s second-largest planet, Saturn, in 2017, yet its incredible mission is still revealing new information.

Findings from Cassini’s data, published in the journal Nature Astronomy, revealed “that Titan rapidly migrates away from Saturn on a timescale of roughly 10 billion years, corresponding to a tidal quality factor of Saturn of Q ≃ 100, which is more than a hundred times smaller [faster] than most expectations.”