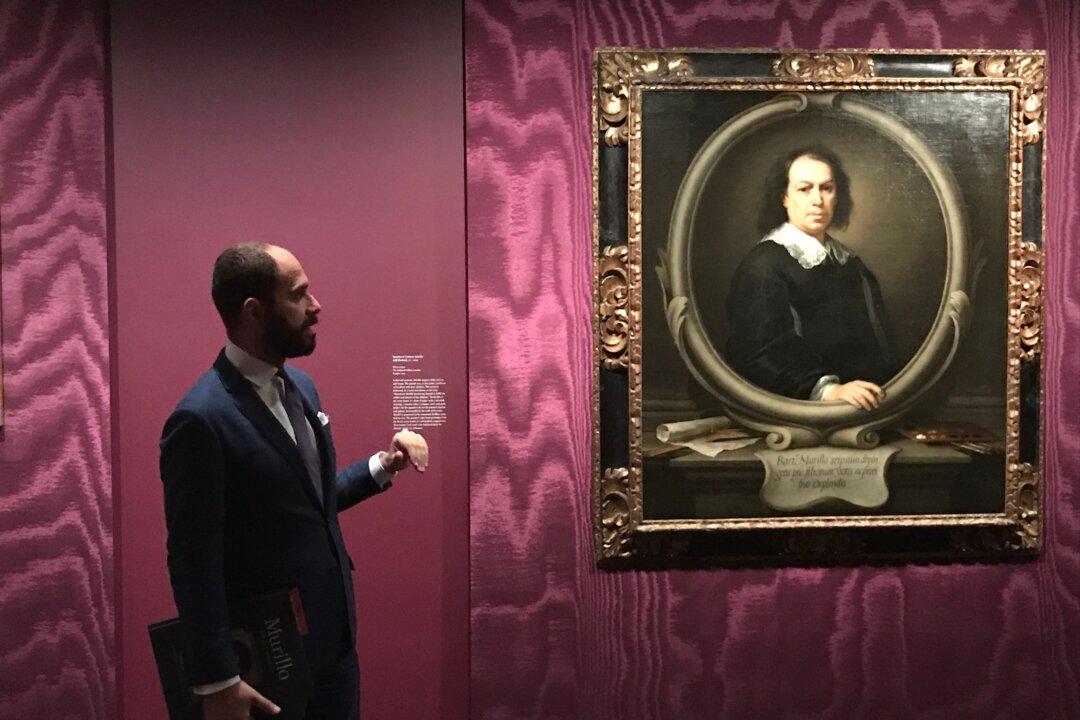

NEW YORK—Best known for his religious and genre paintings of street urchins, the Golden Age Spanish master, Bartolomé Esteban Murillo (1617–1682) left us with two very strange and unique self-portraits, painting his own image within painted stone frames—one at the beginning of his flourishing career in his 30s (circa 1650–55) and the other about two decades later (circa 1670). The artistic conceit of setting himself in stone and emerging beyond the painted frame within the actual frame of his paintings served him well in reaching across time.

In celebration of the 400th anniversary of the artist’s birth, The Frick Collection opened the exhibition “Murillo: Self-Portraits,” running through Feb. 4, 2018. The exhibition will later travel to London’s National Gallery (Feb. 28–May 21, 2018).