Beatrix Potter’s “Peter Rabbit” first emerged in a picture letter to 4-year-old Noel Moore, the son of her former governess. It began: “I don’t know what to write to you so I shall tell you a story.”

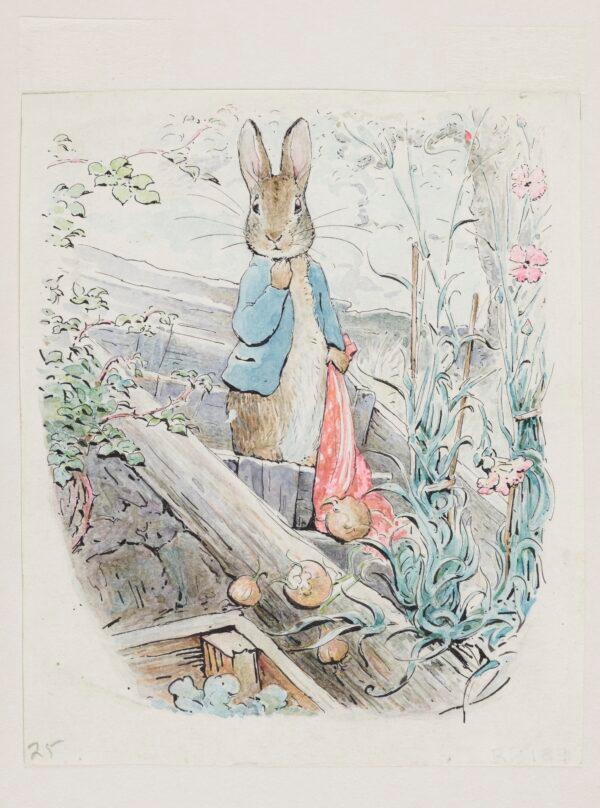

"Peter With Handkerchief," 1904, by Beatrix Potter. A watercolor and pencil book illustration for "The Tale of Benjamin Bunny." National Trust. National Trust images