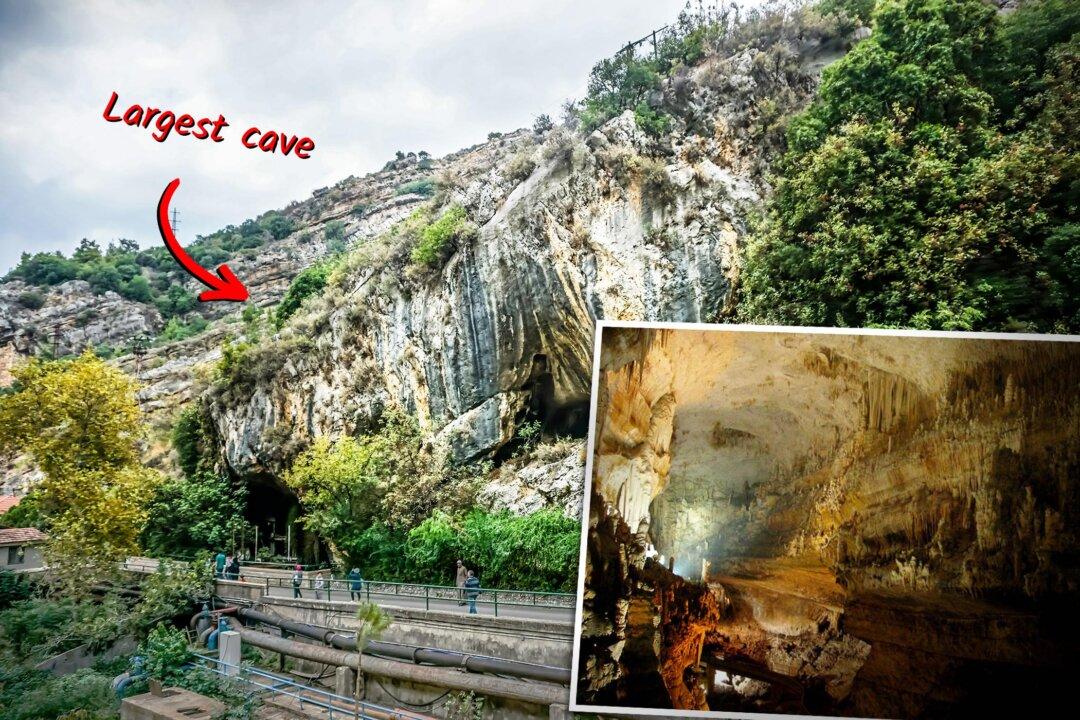

The gunshot fired by an American missionary marked the discovery of a national treasure deep underground.

In 1836, while exploring the Nahr El-Kalb River valley about 11 miles north of Beirut, Lebanon, the missionary William Thompson saw a trickle of water flowing from a fissure in the rocks and he set about investigating.