One needn’t look much further than the Sistine Chapel to know that Michelangelo spent many hours contemplating eternity. In addition to his art, his poetry shows his mind was similarly engaged. His reflections extend beyond how we can achieve eternal life to what it will look like, and his verses paint for us a picture of what he thought it would be.

Michelangelo’s Poems: Painting a Picture of Immortality

The renowned artist of the Renaissance was also a poet of some repute as seen in these verses of physical beauty.

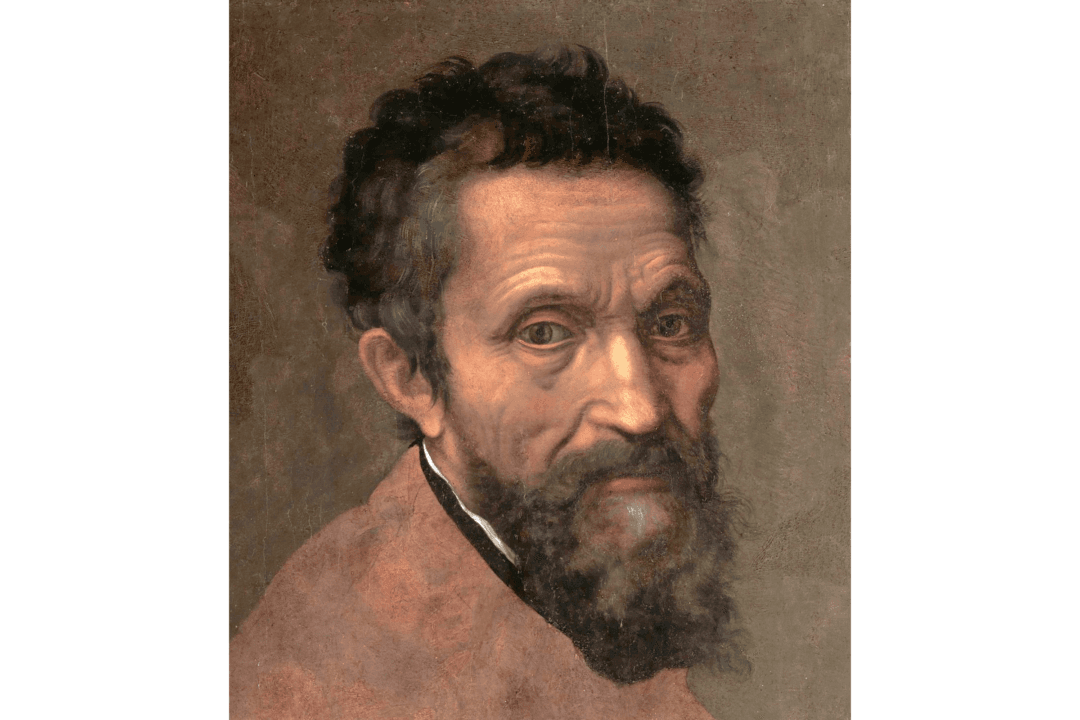

Michelangelo, 1545, by Daniele da Volterra. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Michelangelo wasn't only one of the greatest artists who ever lived, but also a well-known poet in his day. Public Domain