NEW YORK—Albert Einstein once said, “I have no special talent. I am only passionately curious.”

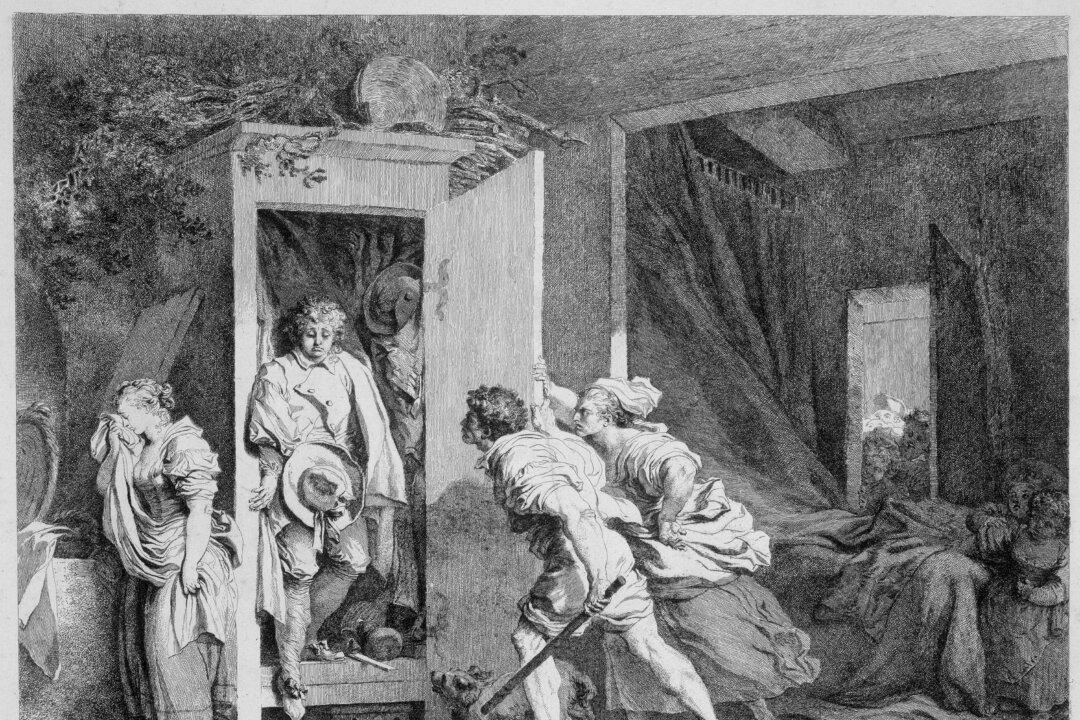

This sentiment could have been echoed by any of the French painters and art connoisseurs who tried their hand at etching during the 18th Century. Their works, many masterful, some clearly first forays, are the subject of the Metropolitan Museum’s new exhibit.

For these individuals, etching was a medium they were exposed to informally. It was not taught in ateliers but rather thought of as a trade. Some made a couple etchings and gave it up; others made an art of it. Jean-Baptiste Le Prince considered his personal aquatint technique superb and tried to sell the secrets.

“Admittedly, some of them are clumsy, and it doesn’t come easily to them,” said curator Perrin Stein. “Some artists have great graphic skills, and it translates. [Jean-Honoré] Fragonard is one of the great draftsmen of the century, so when he thinks, and thinks about creating images with line, he can do it.”

Seeing these amazingly detailed works reminds us of the original meaning of “amateur.” Back then, the word connoted a pure creative drive. Skilled amateurs did not pursue their craft for a living, but often possessed as much finesse as someone who did.

It’s evident that the best of the exhibited artists—who include Fragonard, Antoine Watteau, and François Boucher—had strong understandings of line and contour, light and shade. Even the darkest areas of well executed etchings are never completely black, but consist of a dense net of hatchings.

Jean-Baptiste Marie Pierre’s 1735 etching, “The Chinese Masquerade,” shows a procession of French men and women having a grand old time in ornate and outlandish costumes. Amazingly, this was his first etching.

The Met’s Wendy Thompson explains the process of creating an etching in an essay on the Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History:

“A plate of metal is first covered with a layer of acid-resistant varnish or wax, called the ‘ground.’ The artist then scratches through the ground with an etching needle to expose the metal beneath. When the design is complete, the plate is dipped in acid, which eats away the lines where the metal has been exposed. The depth of the lines depends on the length of time the plate is exposed to the acid. Once the ground has been removed, the metal plate, with its incised lines, can be printed in the same way as any intaglio plate.”

All this is done in mirror image. An example of a partially etched copper plate is part of this exhibit.

Etching’s predecessor, engraving, requires a greater degree of physical control because lines have to be carved directly out of the metal plate. Because etching is akin to drawing, artists naturally gravitated to it, Stein said.

The exhibit also explores amateur prints that were created for sale, prints made by art collectors who took up etching to further their appreciation of art, and the various paths these individuals took to explore a field hitherto dominated by professional printmakers.

These prints remind us what can be accomplished with a little curiosity, a lot of passion, and next to no professional training.

Artists and Amateurs: Etching in 18th-Century France

Oct. 1, 2013–Jan. 5, 2014

Galleries for Drawings, Prints, and Photographs, 2nd floor

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

1000 Fifth Avenue

New York, New York 10028

212-535-7710

www.metmuseum.org

Suggested admission $12–$25