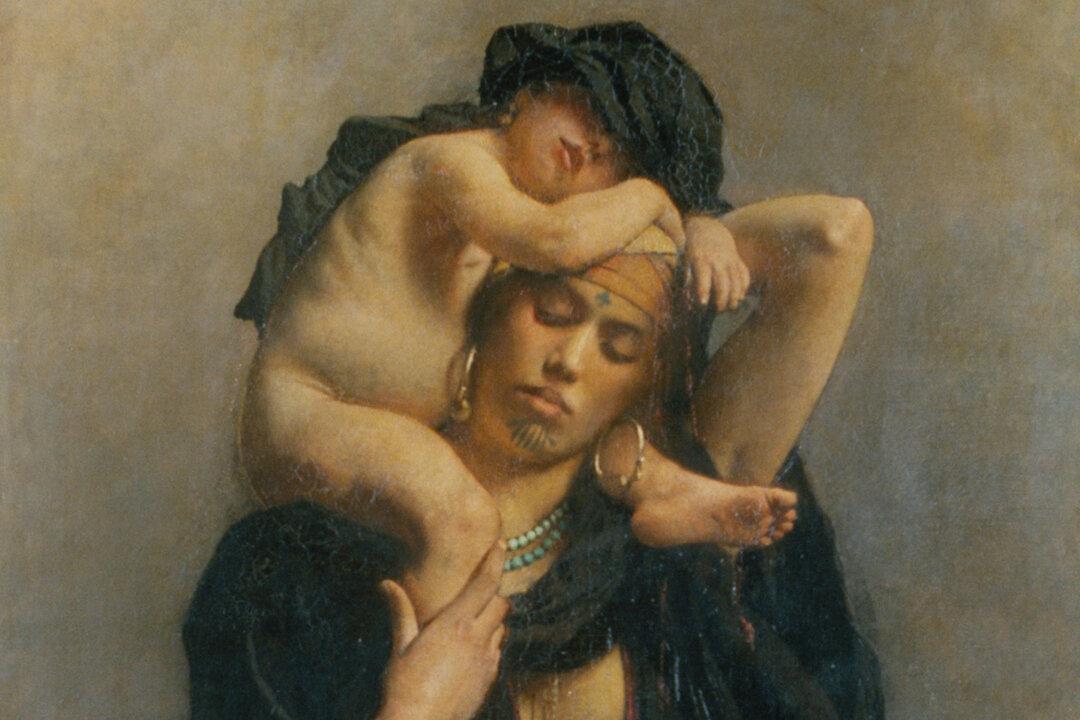

“An Egyptian Peasant Woman and Her Child” is a life-sized painting of a farmer’s wife carrying her sleeping child on her shoulders. It is an intimate slice of life scene expressed by the French painter Painter Léon Bonnat amid a phase of transition and expansion in Egyptian history.

The canvas depicts a female “fellah” (a peasant or farmer in Arabic-speaking regions), clothed in an obsidian “galabeya” (a long, flowing, loose garment made of lightweight fabric suitable for agricultural labor), with her eyes closed, bearing the weight of her naked child. An extension of the mother’s garment is draped over the top half of the child’s face, obscuring his eyes.