According to a list provided by the American Film Institute, the third-best film score ever composed for a Hollywood movie was written by a young Frenchman who couldn’t read music until age 15. A percussionist by training, the Frenchman’s most extensive experience prior to scoring this masterpiece was 12 years of penning background scores for Parisian theater productions. Yet, anyone who has heard his music might well assume that the composer was a violinist or pianist with developed skills in shaping long, luxurious melodies. The score in question is that for “Lawrence of Arabia,” and the young Frenchman was Maurice Jarre (1924–2009).

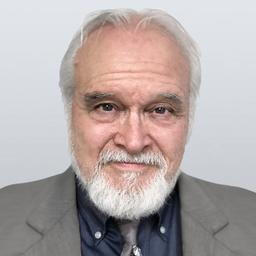

Film composer Maurice Jarre (L), receiving a César Award in honor of his career, stands beside French choreographer Maurice Béjart at the César ceremony in Paris on Feb. 22, 1986. Jarre, Oscar-winning composer for films including "Doctor Zhivago" and "Lawrence of Arabia," also wrote symphonic music and music for theater and ballet. Pascal George/AFP via Getty Images