Some sculptures that celebrate America’s past are well known to most of us. The Washington Monument, that obelisk shooting up 500 feet above our nation’s capital, is one of these. The Lincoln Memorial appears on the $5 bill and the penny. Movies ranging from “Planet of the Apes” to “Splash” have showcased New York’s Statue of Liberty, and the dramatic Marine Corps War Memorial is a military icon. Above South Dakota’s Black Hills rises Mount Rushmore with its massive figures of George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln, and Theodore Roosevelt.

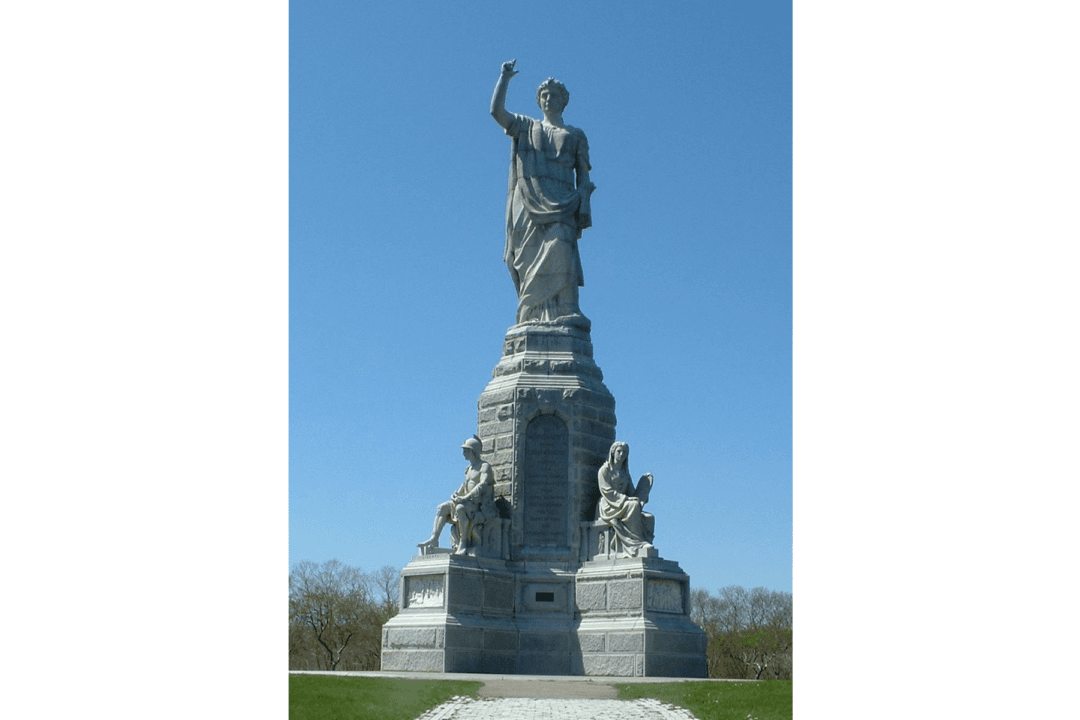

Hundreds of other lesser-known statues dot the American landscape, telling their stories of the past in bronze or stone to passersby. Some of these qualify as works of art, yet they lack the grandeur, the drama, or the charisma of meaning to imprint themselves on the national consciousness. In some cases, such as South Dakota’s Crazy Horse Memorial, location may hinder a sculpture’s popularity.