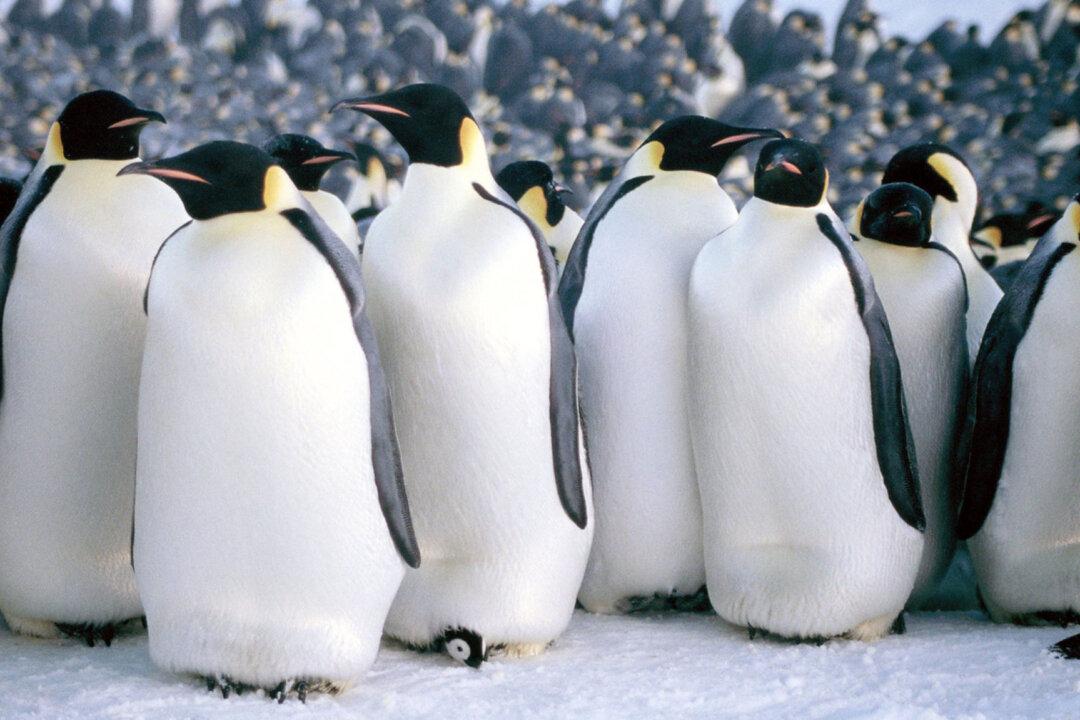

G | 1h 20m | Documentary, Family, Nature, Mystery | 2005

As with the recently reviewed “Microcosmos” and “Winged Migration,” “March of the Penguins” (“March”) is an art house, French-produced nature documentary from the 2000s that defied all industry expectations and became a huge hit with mainstream audiences the world over.