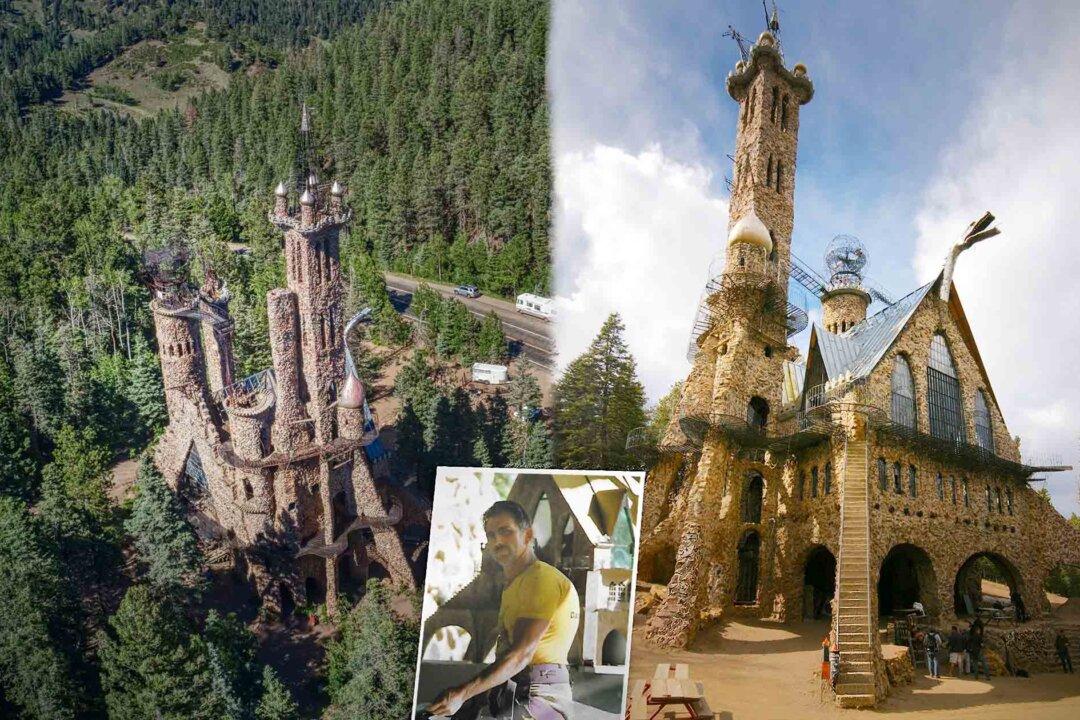

They wanted a castle. So Jim Bishop was going to build them a castle.

It was 1969 when the ornamental ironworker in his late 20s set out building a stone cottage near Pueblo, Colorado, with the help of his father, intending to make a home out of a shack. But what began as a construction project turned into a beacon for freedom some 50 years in the making. Bishop Castle would be born from it.