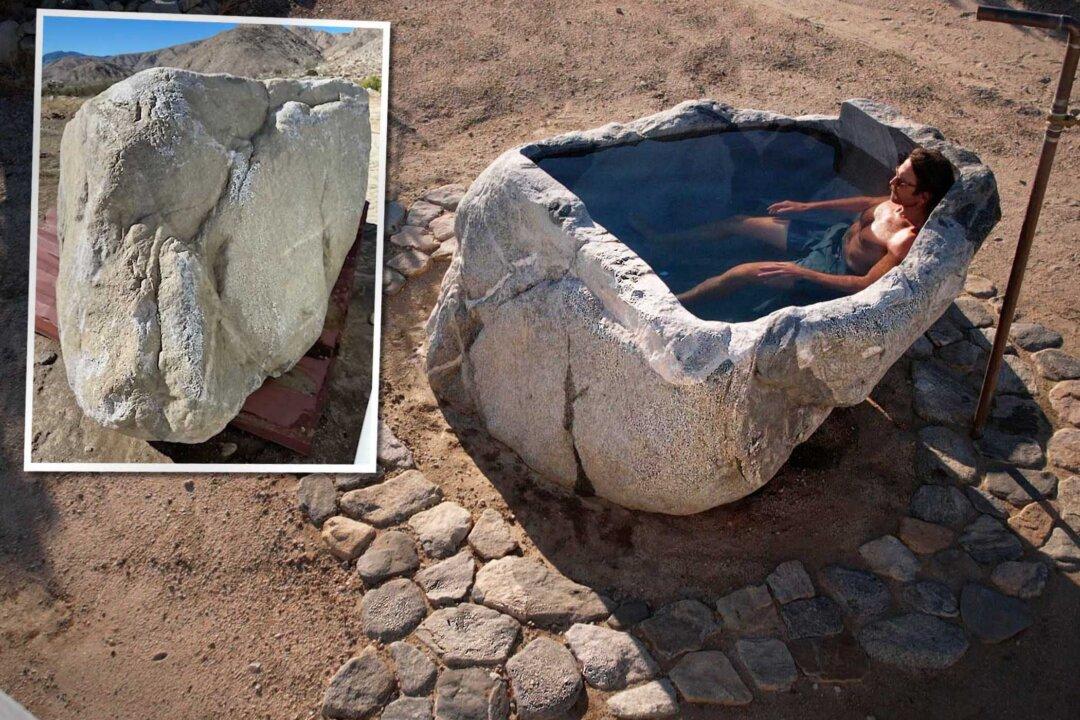

One day, a man in Southern California was digging in the desert and found a stone of extraordinary size and character—he saw a prize inside it that most people would miss.

With his backhoe, James Lostlen flipped over that irregularly-shaped boulder that weighed nearly as much as his machine and a vision of what could be appeared in his mind: