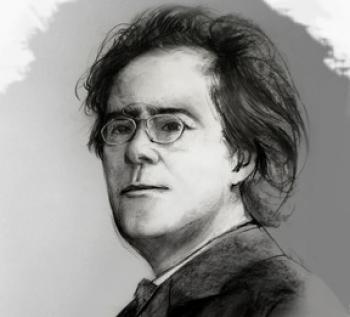

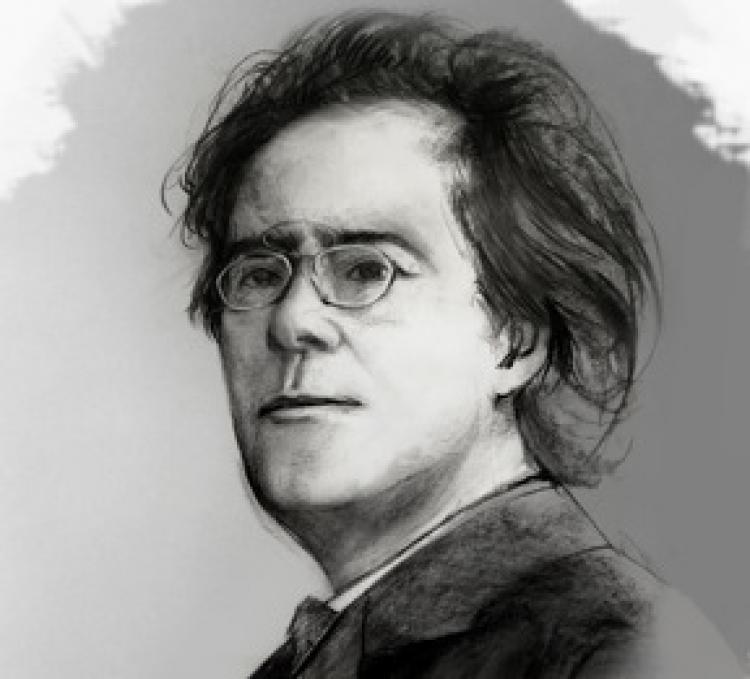

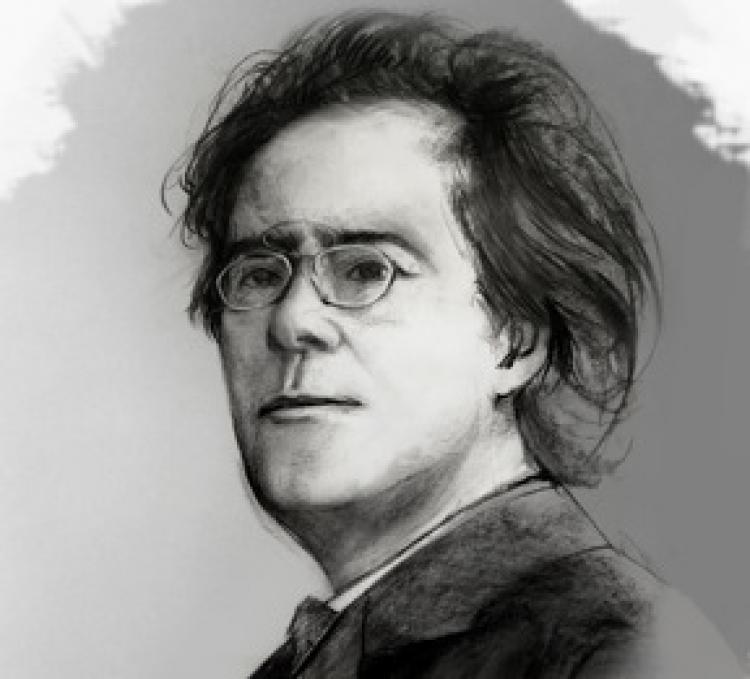

In this day and age, Gustav Mahler (1860–1911) is known as one of the most important symphonic composers of all times. In his day, he was better known as an orchestral conductor.

The truth is that he displayed enormous energy and commitment as principal conductor of the Vienna Opera and later in New York as principal conductor of the Metropolitan Opera House and the New York Philharmonic. As a conductor, Mahler was outstanding in his interpretations of opera, but in his creative vein, he was outstanding as a symphonic composer and writer of beautiful song cycles for voice with symphony orchestra accompaniment.

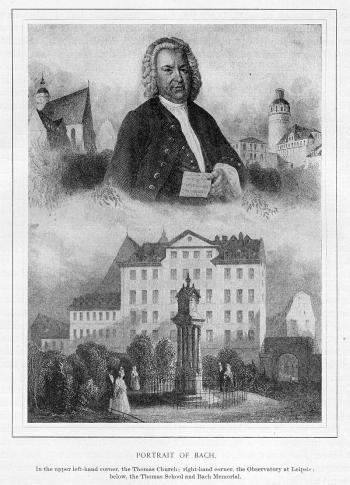

In fact, Mahler repeatedly included the human voice as a vital element in his symphonic works. Brahms, Schubert, and Schumann did not do so in their symphonies, and Beethoven only included voice in the last of his symphonies, the mythic Ninth. Nevertheless, there are those who argue that Mahler’s most satisfying works are not his nine symphonies, but his lieder—the song cycles accompanied by orchestra.

I don’t know if I agree with that opinion. I just listened again to a recording of Mahler’s second symphony, the “Resurrection.” It was Leonard Bernstein’s version with the London Symphony Orchestra and the wonderful Janet Baker as soloist.

The last portion of the piece is as if the gates to paradise are thrown open. But you have to pay a heavy toll to get there: There is the desperation, fear, and morbid quality that the first movement transmits. (It was originally planned as an independent piece, or symphonic poem, which he titled “Totenfeier,” or “Funeral Celebration.”) Then follow the melancholy of the second movement and the banality of daily life depicted with irony in the third. Finally, we arrive at sublime spiritual peace in the last movement.

If the overblown dimensions of his nine symphonies (ten, if you count the extraordinary Adagio that he titled Symphony but never concluded with more movements) become an obstacle for some listeners, his song cycles turn out to be much more accessible.

Some beautiful works include “Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen” (“Songs of a Wayfarer”), “Des Knaben Wunderhorn” (“The Knave’s Magic Horn”), and the “Rückertlieder.”

Possibly his very best work is “Das Lied von der Erde” (“The Song of the Earth”), a song cycle based on poems translated from Chinese into German, but with the dimensions and concept of sound more suited to a proper symphony. But to my taste, a real masterpiece is “Kindertotenlieder” (“Songs on the Death of Children”), a piece of compositional genius and tremendous emotional significance as it represents reflections on Mahler’s very own daughter’s death.

When I was a music student, I had the good luck to travel to Chicago on several occasions to hear the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. On one of those occasions, they performed Mahler’s Sixth Symphony under the direction of Günther Herbig. As it was the first time I heard a piece by Mahler played live, I didn’t know what to expect.

The overwhelming wall of sound left me speechless—I’d never heard anything like it in my life. Nor had I ever sat through such a long piece!

The next year, I went back to hear the fabulous Georg Solti conducting the Fifth Symphony live. It was pure drama; I haven’t experienced anything like it since. The quality and sound production of that orchestra were peerless; in fact, there are musicians in the profession nowadays who refer to the legendary Chicago Symphony brass section of that time as the “Dream Team.”

Now I’ve been a professional orchestral musician for 20 years, and to tell the truth, playing Mahler’s works is quite an experience.

One time, the management of my orchestra programmed the Eighth Symphony, the “Symphony of a Thousand” as it is often called, because of the number of performers required. If the dimensions in time of his works are exaggerated, the personnel required for the Eighth is madness. (It’s not literally a thousand people, but it’s not strange to see over 400 people on stage to do the piece).

They “hired” an additional symphony orchestra, which arrived with all hands, plus three choirs, a group of vocal soloists, and we played the symphony together. It was a truly memorable experience to form part of that enormous flood of sound.

Dichotomies abounded in Mahler’s life just as in his music. He was Jewish but renounced Judaism so he could take the position as principal conductor of the Vienna Opera. After the death of his daughter, and with the growing anti-Semitism, he left his country to cross the Atlantic and establish himself in the United States, and he only returned when his health started to deteriorate. So he lived between two worlds: complete joy and depression, heaven and earth.

The spiritual dimension in his music is made clear in many ways. The breadth of sound makes it seem that he is always trying to communicate with God. The constant handling of tension throughout his works points to a constant searching, and to the restlessness of a soul that knows of Heaven’s existence but is lost. There is a multitude of times when Mahler writes chorales for the orchestra that are close reflections of sacred Church music, and it’s as if he was a novelist quoting the Bible indirectly.

On the other hand, Mahler makes use of the popular music of his time to portray the vulgar aspect of life. He himself said that a symphony should be an entire world. In his created worlds, you can find waltzes, ländlers, minuets, and other types of popular music, but he distorts them with such irony that they become grotesque and much more morbid than the dances on which they are based. Sometimes the music becomes wild, manic, bedeviled, enraged, tortured like the soul of its very own author.

Extreme contrasts of emotional states are typical of Mahler, and the changes from one mood to another can be quite abrupt. Banality and vulgarity live side by side with divinity. This paradox, to my mind, is the essence of what Mahler transmits, and it lends a kind of dynamism that makes him so interesting.

Nevertheless, he was misunderstood during his lifetime and he himself correctly predicted that his works would take another 50 years after his death to become accepted by the public.

The truth is that he displayed enormous energy and commitment as principal conductor of the Vienna Opera and later in New York as principal conductor of the Metropolitan Opera House and the New York Philharmonic. As a conductor, Mahler was outstanding in his interpretations of opera, but in his creative vein, he was outstanding as a symphonic composer and writer of beautiful song cycles for voice with symphony orchestra accompaniment.

In fact, Mahler repeatedly included the human voice as a vital element in his symphonic works. Brahms, Schubert, and Schumann did not do so in their symphonies, and Beethoven only included voice in the last of his symphonies, the mythic Ninth. Nevertheless, there are those who argue that Mahler’s most satisfying works are not his nine symphonies, but his lieder—the song cycles accompanied by orchestra.

The ‘Resurrection’ and the Song Cycles

I don’t know if I agree with that opinion. I just listened again to a recording of Mahler’s second symphony, the “Resurrection.” It was Leonard Bernstein’s version with the London Symphony Orchestra and the wonderful Janet Baker as soloist.

The last portion of the piece is as if the gates to paradise are thrown open. But you have to pay a heavy toll to get there: There is the desperation, fear, and morbid quality that the first movement transmits. (It was originally planned as an independent piece, or symphonic poem, which he titled “Totenfeier,” or “Funeral Celebration.”) Then follow the melancholy of the second movement and the banality of daily life depicted with irony in the third. Finally, we arrive at sublime spiritual peace in the last movement.

If the overblown dimensions of his nine symphonies (ten, if you count the extraordinary Adagio that he titled Symphony but never concluded with more movements) become an obstacle for some listeners, his song cycles turn out to be much more accessible.

Some beautiful works include “Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen” (“Songs of a Wayfarer”), “Des Knaben Wunderhorn” (“The Knave’s Magic Horn”), and the “Rückertlieder.”

Possibly his very best work is “Das Lied von der Erde” (“The Song of the Earth”), a song cycle based on poems translated from Chinese into German, but with the dimensions and concept of sound more suited to a proper symphony. But to my taste, a real masterpiece is “Kindertotenlieder” (“Songs on the Death of Children”), a piece of compositional genius and tremendous emotional significance as it represents reflections on Mahler’s very own daughter’s death.

Experiencing Mahler’s Music

When I was a music student, I had the good luck to travel to Chicago on several occasions to hear the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. On one of those occasions, they performed Mahler’s Sixth Symphony under the direction of Günther Herbig. As it was the first time I heard a piece by Mahler played live, I didn’t know what to expect.

The overwhelming wall of sound left me speechless—I’d never heard anything like it in my life. Nor had I ever sat through such a long piece!

The next year, I went back to hear the fabulous Georg Solti conducting the Fifth Symphony live. It was pure drama; I haven’t experienced anything like it since. The quality and sound production of that orchestra were peerless; in fact, there are musicians in the profession nowadays who refer to the legendary Chicago Symphony brass section of that time as the “Dream Team.”

Now I’ve been a professional orchestral musician for 20 years, and to tell the truth, playing Mahler’s works is quite an experience.

One time, the management of my orchestra programmed the Eighth Symphony, the “Symphony of a Thousand” as it is often called, because of the number of performers required. If the dimensions in time of his works are exaggerated, the personnel required for the Eighth is madness. (It’s not literally a thousand people, but it’s not strange to see over 400 people on stage to do the piece).

They “hired” an additional symphony orchestra, which arrived with all hands, plus three choirs, a group of vocal soloists, and we played the symphony together. It was a truly memorable experience to form part of that enormous flood of sound.

Mahler’s Life Between Two Worlds

Dichotomies abounded in Mahler’s life just as in his music. He was Jewish but renounced Judaism so he could take the position as principal conductor of the Vienna Opera. After the death of his daughter, and with the growing anti-Semitism, he left his country to cross the Atlantic and establish himself in the United States, and he only returned when his health started to deteriorate. So he lived between two worlds: complete joy and depression, heaven and earth.

The spiritual dimension in his music is made clear in many ways. The breadth of sound makes it seem that he is always trying to communicate with God. The constant handling of tension throughout his works points to a constant searching, and to the restlessness of a soul that knows of Heaven’s existence but is lost. There is a multitude of times when Mahler writes chorales for the orchestra that are close reflections of sacred Church music, and it’s as if he was a novelist quoting the Bible indirectly.

On the other hand, Mahler makes use of the popular music of his time to portray the vulgar aspect of life. He himself said that a symphony should be an entire world. In his created worlds, you can find waltzes, ländlers, minuets, and other types of popular music, but he distorts them with such irony that they become grotesque and much more morbid than the dances on which they are based. Sometimes the music becomes wild, manic, bedeviled, enraged, tortured like the soul of its very own author.

Extreme contrasts of emotional states are typical of Mahler, and the changes from one mood to another can be quite abrupt. Banality and vulgarity live side by side with divinity. This paradox, to my mind, is the essence of what Mahler transmits, and it lends a kind of dynamism that makes him so interesting.

Nevertheless, he was misunderstood during his lifetime and he himself correctly predicted that his works would take another 50 years after his death to become accepted by the public.