The Russian poet Anna Akhmatova is too tragic and striking a figure ever to be forgotten. A famous portrait depicts her in a midnight-blue dress and brilliant yellow shawl beside an objectivist arrangement of lighter blue hydrangeas. Nose aquiline and eyes contemplative under the signature black fringe, she is utterly transfixing. Yet much of our knowledge of Akhmatova is due to the self-effacing journals of a less-remembered woman, Lydia Chukovskaya, who brought her friendship, food, and unfailing support.

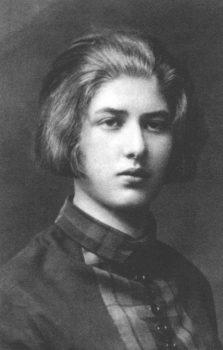

Lydia Chukovskaya in 1926. KateSharpleyLibrary.net