What things should we be willing to die for?

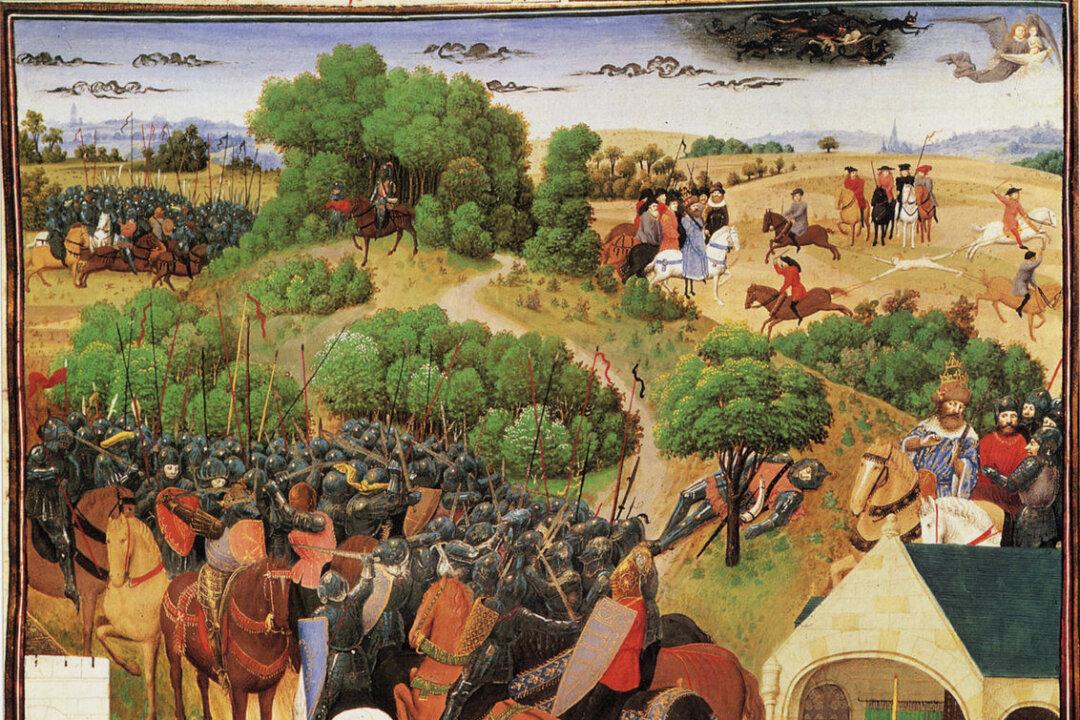

The 11th-century epic poem “The Song of Roland” by a poet named Turoldus engages this question. The poem is a type of traditional French narrative called a “chanson de geste” (“song of heroic deeds”). It tells of the death of Emperor Charlemagne’s nephew, Count Roland, during the Battle of Roncevaux Pass in A.D. 778. The work is loosely based on historical events, using the framework of Charlemagne’s wars as a means of exploring hierarchy, loyalty, the crusading spirit, and the conflict between good and evil.