All great authors in some way explore the question: What does it mean to be human? Few writers do this better than Shakespeare, and, I would argue, few of Shakespeare’s plays rival “The Tempest” in its ability to display both the depths to which human nature can sink and the heights to which it can rise.

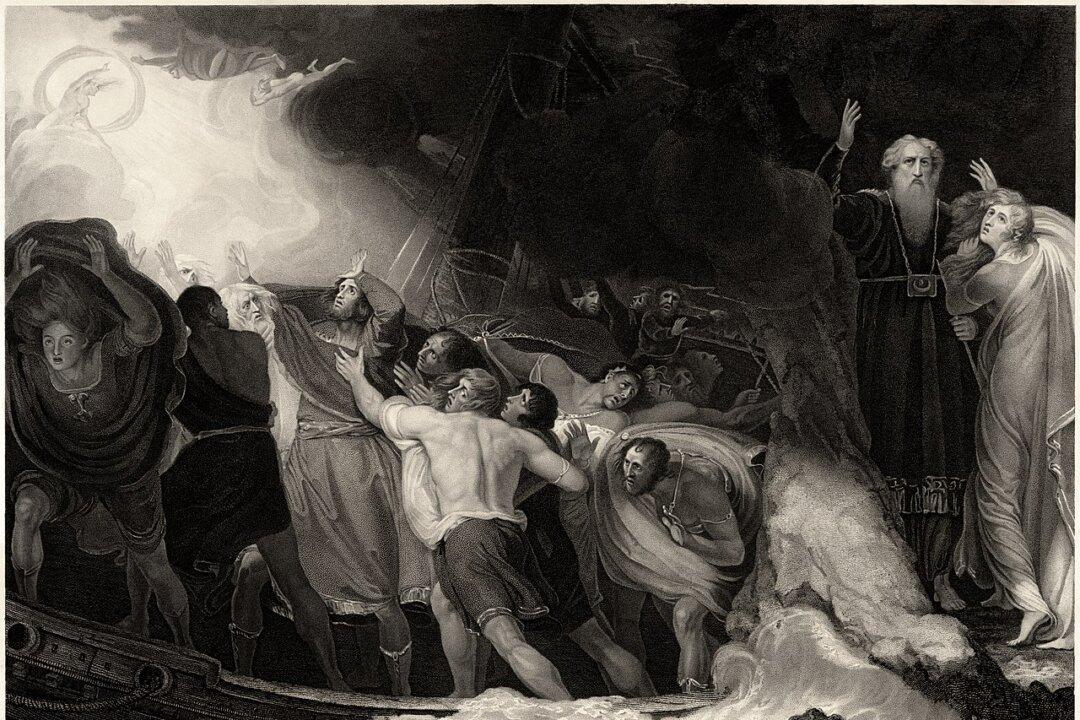

“The Tempest” tells the tale of a magician, Prospero, who has been exiled to a mysterious island along with his daughter, Miranda. Miranda has grown up on the island, her only companions being her father, the creature Caliban, and various spirits, such as Ariel, who serve her father.