Tucked away in the West End neighborhood of Tuscaloosa, and next to what used to be a hugely popular local attraction, Maggie’s Diner, sits a humble white brick barbershop, complete with a spinning barber pole. From the outside, the shop does not hint at the treasures found inside. Beyond the old barbershop chair, and beyond the mirrors and trimmers and towels and hair solutions and shaving foam, a collection of photographs from the civil rights movement, newspaper clippings, and memorabilia from the 1960s is hanging on the walls. Among the old black-and-white photographs—turning yellow with the passage of time—are several of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and other movement leaders during their time in Alabama.

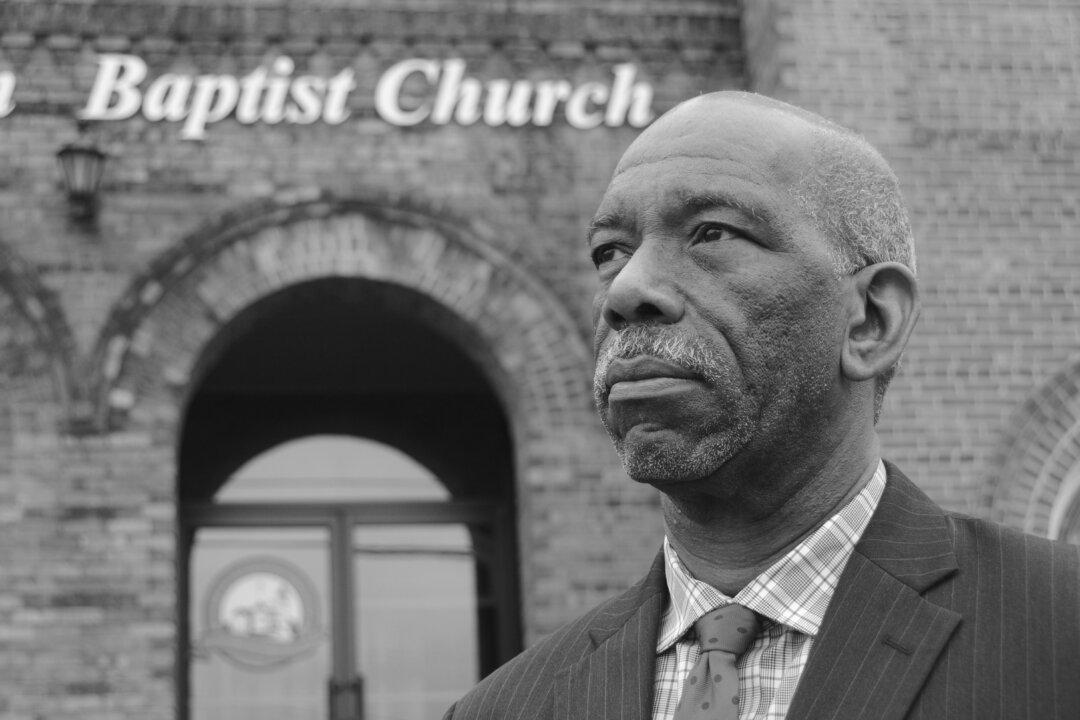

The barbershop was owned by Rev. Thomas Linton, who passed away on May 14, 2020, but his legacy in preserving the history of the civil rights movement will remain. His role in the Bloody Tuesday events in Tuscaloosa will endure as a bright light in the struggle for equality. Linton’s Barbershop served as a shelter for protesters on Tuesday, June 9, 1964. The protesters had wanted to make a stand against segregated drinking fountains and restrooms. They were met with furious white police officers and citizens outside First African Baptist Church, which was located near the barbershop.