Having the heart of a warrior, Lewis Millett joined the U.S. military before he officially became an adult. During his military career that lasted over three decades, Millett earned several awards for his valor in three of America’s major wars.

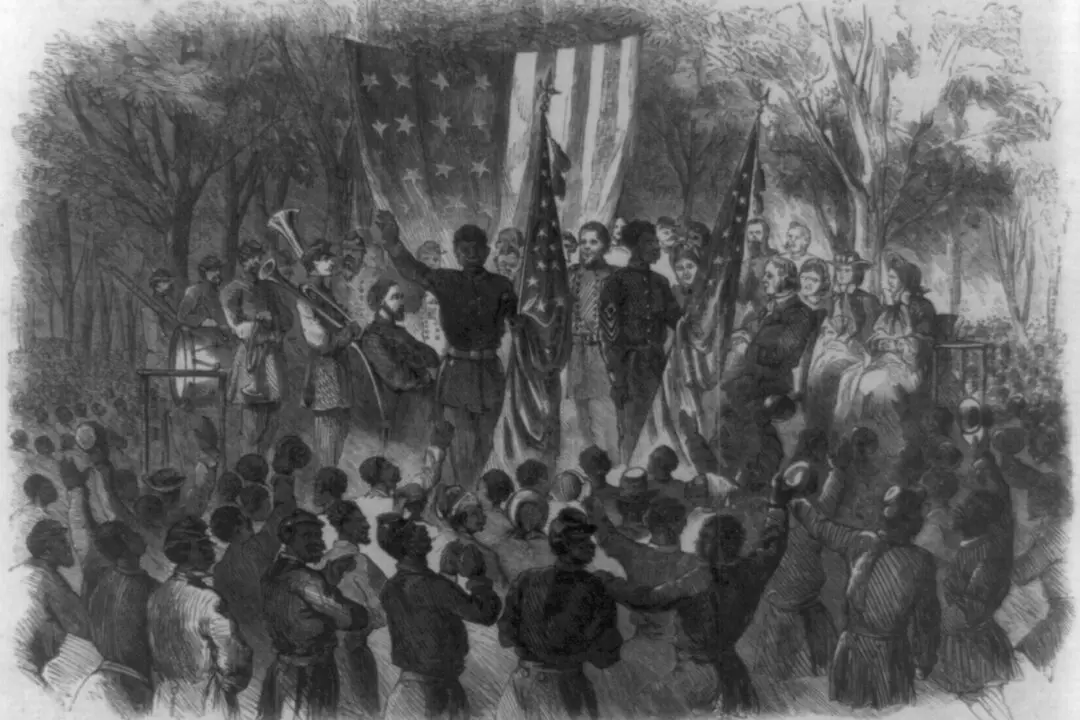

Millett was born in Maine in 1920 and moved to Massachusetts with his mother after his parents divorced. The young man grew up hearing battlefield stories about a grandfather who served in the Civil War and an uncle who fought in World War I.